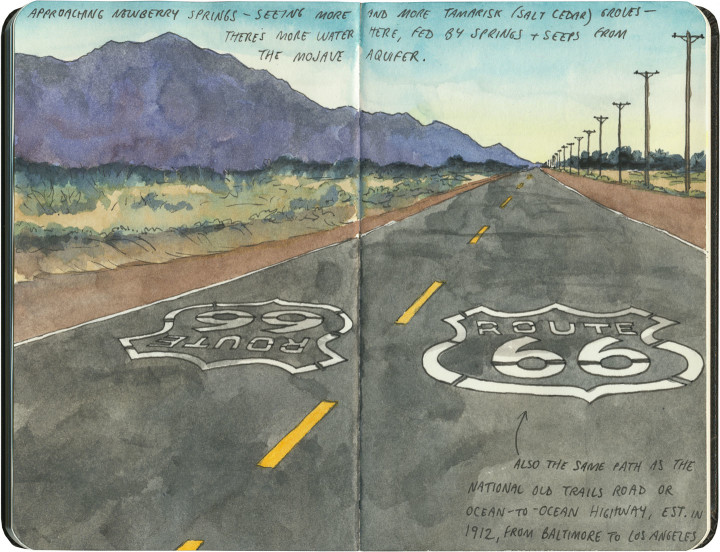

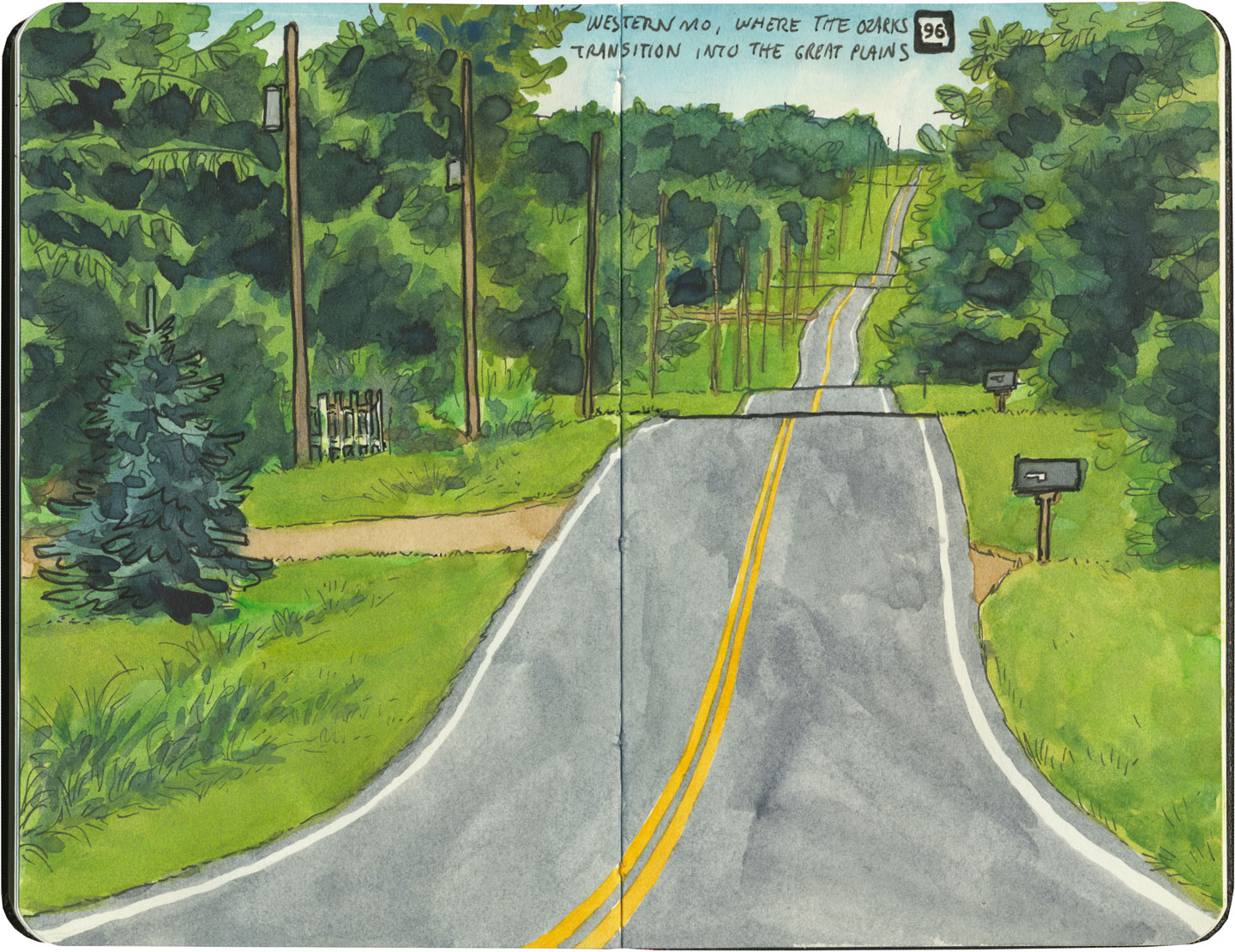

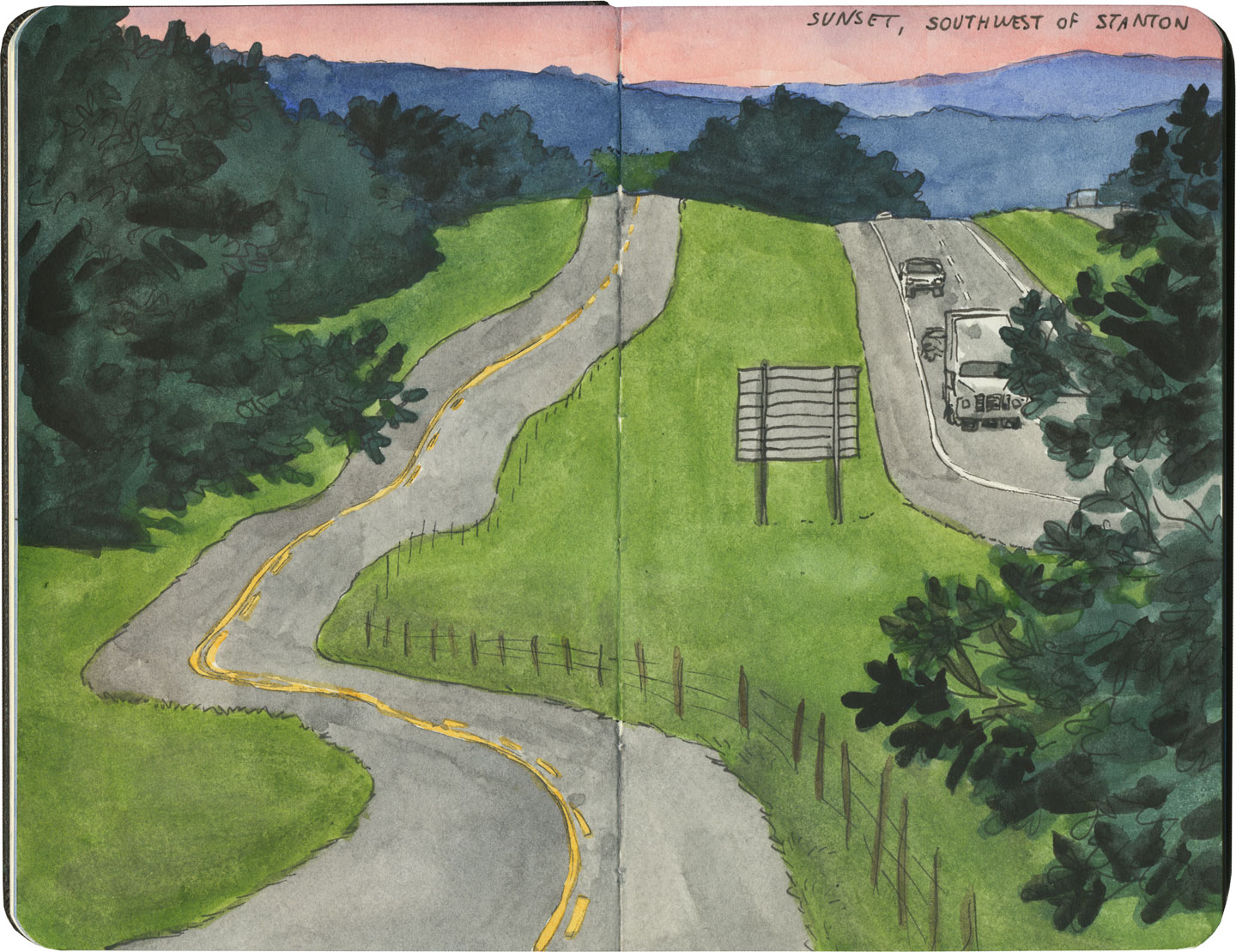

This post is part of an ongoing series called 66 Fridays, which explores the wonders of old Route 66. Click on the preceding “66 Fridays” link to view all posts in the series, or visit the initial overview post here.

If you travel Route 66, you’re sure to come across the name of Fred Harvey. If you haven’t heard of him, you’re far from alone. Yet Harvey and his commercial empire had a lot to do with creating, collecting and curating that slice of Americana we call the Southwest.

If I were throw another name at you, though, I bet you’d be able to place it: Howard Johnson. That’s right, the hospitality magnate who, in the 1960s and 70s, controlled the largest restaurant chain in the United States. Well, I’m not knocking Johnson (or all that fabulous midcentury decor), but Harvey did it first, and best.

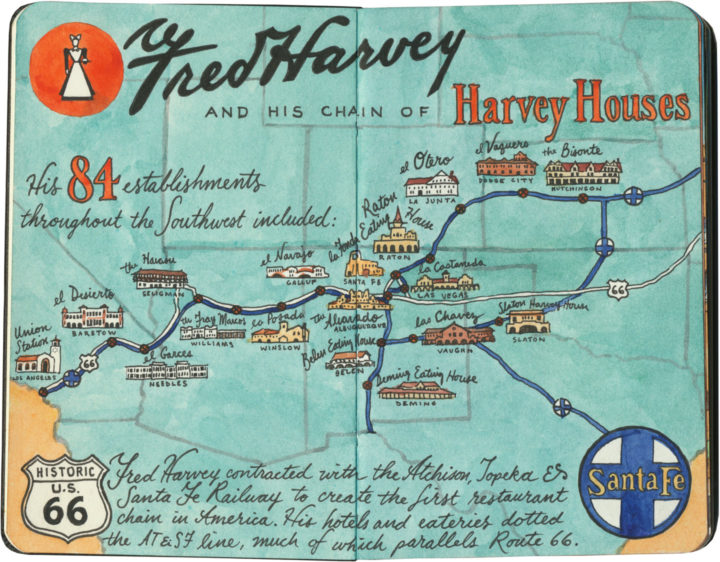

Harvey got his start in the late 1870s, when the West was still very much a wild place, and the railroads were busy cutting new paths over the old overland trade routes. Harvey was revolted by the food the railroad companies offered their passengers—he figured if eastern travelers could access the same quality of cuisine they’d find in a New York City restaurant, they’d get over their fear of “roughing it” and head West in style. His employer, the Burlington Railroad, turned him down, but the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway saw merit in the idea. Harvey signed a contract with AT&SF, and the first American restaurant chain was born.

Before long, Harvey had added hotels and tour services to his repertoire, and by the early twentieth century there were “Harvey Houses” scattered all over the Southwest. Some of his best-known properties still stand—including nearly all of the historic buildings that comprise the South Rim complex at the Grand Canyon.

Early conservationists like Teddy Roosevelt were horrified by the prospect of commercializing the Grand Canyon, yet one could easily argue that if Fred Harvey hadn’t done it, someone else most assuredly would have (and they did! Google the mayhem that is Ralph Henry Cameron sometime, if you’re curious).

One vote in favor of Harvey was that each of his establishments was thoughtfully designed to be at once beautiful, well-made, reflective of its natural surroundings and sensitive to its area’s cultural heritage. (I’m sure that last box wasn’t checked as well as it might have been, but considering the era in which these places were designed, the fact that any cultural sensitivity came about at all is nothing short of astonishing.)

And we have one person to thank for much of that:

That’s right: Fred Harvey’s right-hand man was a woman. And it’s Mary Jane Colter’s style and sensibility that come through in the most memorable Harvey Houses. She is the one who created much of that unified “look” that we associate with the American Southwest. And that’s because she did her research—she looked at all the different regional architectural styles of the various Native cultures of the region, and blended them with the popular architectural styles of the day: Arts & Crafts, Mission, and various revivals of European and even North African traditions.

Colter went one step further, and did something that was way ahead of her time: she actually hired Native artists and craftspeople to complete many of the details on and in her buildings. She worked most often with Hopi painter Fred Kabotie, who contributed elements like the murals at the Painted Desert Inn and various interior details at Hopi House. In working with artists like Kabotie, Colter’s buildings have an authenticity to them that, along with their craftsmanship, elevates them way above your average tourist trap.

I didn’t know any of this before my trip, nor had I ever heard of Fred Harvey before. Luckily for me, many of the surviving Harvey Houses are located along Route 66, so I had ample opportunity to find out—

—and to gaze in wonder at so many architectural treasures still standing along the Mother Road.

Most serendipitous for my Harvey education was our decision to drive the original (and less-traveled) pre-1937 alignment of Route 66, which took us to Santa Fe. For one thing, Santa Fe is home to the most magnificent example of extant Harvey Houses: Hotel La Fonda.

The place is often nicknamed “the oldest hotel in the United States,” but that’s not exactly true. What is true is that an inn or fonda has stood continuously upon this location for over four hundred years. Harvey must have known that particular historical tidbit, because La Fonda doesn’t mess around. Every inch of the place is jam-packed with Harvey’s version of Southwest Americana.

The hotel has been remade and renovated seemingly endlessly over the years, but you can still find traces of its history (and Mary Colter’s interior touches) everywhere.

La Fonda is the place where you learn to recognize the Harvey style—where even if you don’t know the history behind any of it, you’ll still know it when you see it.

The other thing Santa Fe gave me was a glimpse of Harvey’s empire on a micro scale, thanks to the New Mexico History Museum at the Palace of the Governors. Far beyond capitalizing on the idea of a hospitality chain, what Fred Harvey really understood was branding. And branding really isn’t even the right word here: while other hotels might have an “identity,” Harvey went way beyond that. For his employees, he created a culture. For his customers, he created something more akin to mythology.

For an amateur graphic design historian like me, I felt like I’d struck gold at the Palace of the Governors. Their Harvey House exhibit displayed the length, breadth and depth of Harvey branding—beyond any logo, their aesthetic covered everything from letterhead to jewelry to employee pamphlets. Harvey’s penchant for hiring professional artists paid off on every front: every last detail was carefully considered, equally beautiful, and a stand-alone work of art.

And that brings me to the most famous and curious piece of Harvey branding: the Harvey Girl.* A living, breathing icon, the Harvey Girl became the very embodiment of the taming of the West.

Fred Harvey felt that while the romantic idea of the Wild West might be a draw to tourists, its rough-and-tumble connotations would be more of a hinderance than anything else, as wealthy customers viewed western travel as dangerous and uncomfortable. To counteract this notion, Harvey committed to hiring only educated young women from the East and Midwest to wait upon, entertain and guide his guests. The Harvey Girls had to adhere to strict codes of dress, conduct and morality; live in single-sex barracks run by middle-aged den mothers; and sign year-long contracts which forbade them to marry while employed by the Harvey Company. The idea of “civilizing” the West, one genteel lady at a time, was a smash hit, and the Harvey Girl became so iconic that Judy Garland even played one on the silver screen.

What really interests me, however, is that the Harvey Girls—and there were 100,000 of them in all—were the first female workforce in America. The guests may have seen them as mere waitresses, but in reality these were educated women who were responsible for far more than carrying trays or taking orders. Later, as automobiles became popular and Harvey started his Indian Detours auto tour service, Harvey Girls—renamed “Couriers” or even, ugh, Indian Maids—comprised the entire staff of tour guides. Most had college degrees, and each Courier was required to have a working knowledge of local history, botany, geology, archaeology, anthropology, geography, or any other subject the tourists might inquire about.

* Note: Much of my Harvey Girl information comes from Katrina Parks’s wonderful documentary, The Harvey Girls: Opportunity Bound. Excerpts from the documentary are included in the Harvey exhibit at the Palace of the Governors, and it is these that introduced me to Ms. Parks’s work. She is currently working on a new project called The Women on the Mother Road—her website features some of my Route 66 sketches, and I’m excited and honored to be included!

I tell you all of this to illustrate just how far-reaching Fred Harvey’s empire was, how much of modern American history was touched by his ideas. The Harvey Houses weren’t just another hotel chain—they were an astonishing and vast collective work of art. And they were an incredible economic engine that provided work to thousands of people—many of them highly skilled artists, designers, craftspeople, historians, scientists and anthropologists.

The Harvey Company also employed many unskilled laborers, like the Civilian Conservation Corps (one of Franklin Roosevelt’s “Alphabet Soup” agencies founded during the Great Depression), who built and then painted this glass skylight at the Painted Desert Inn.

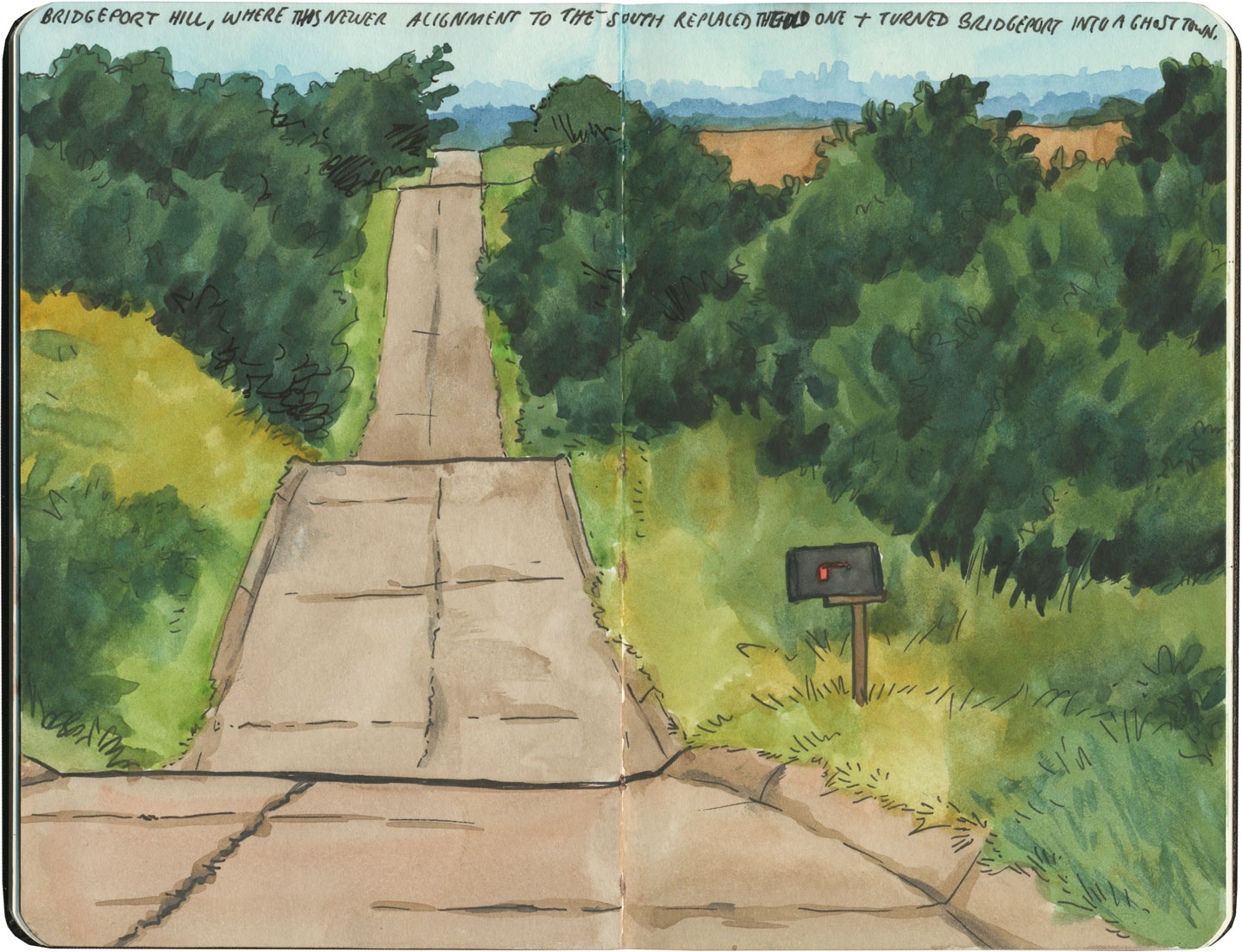

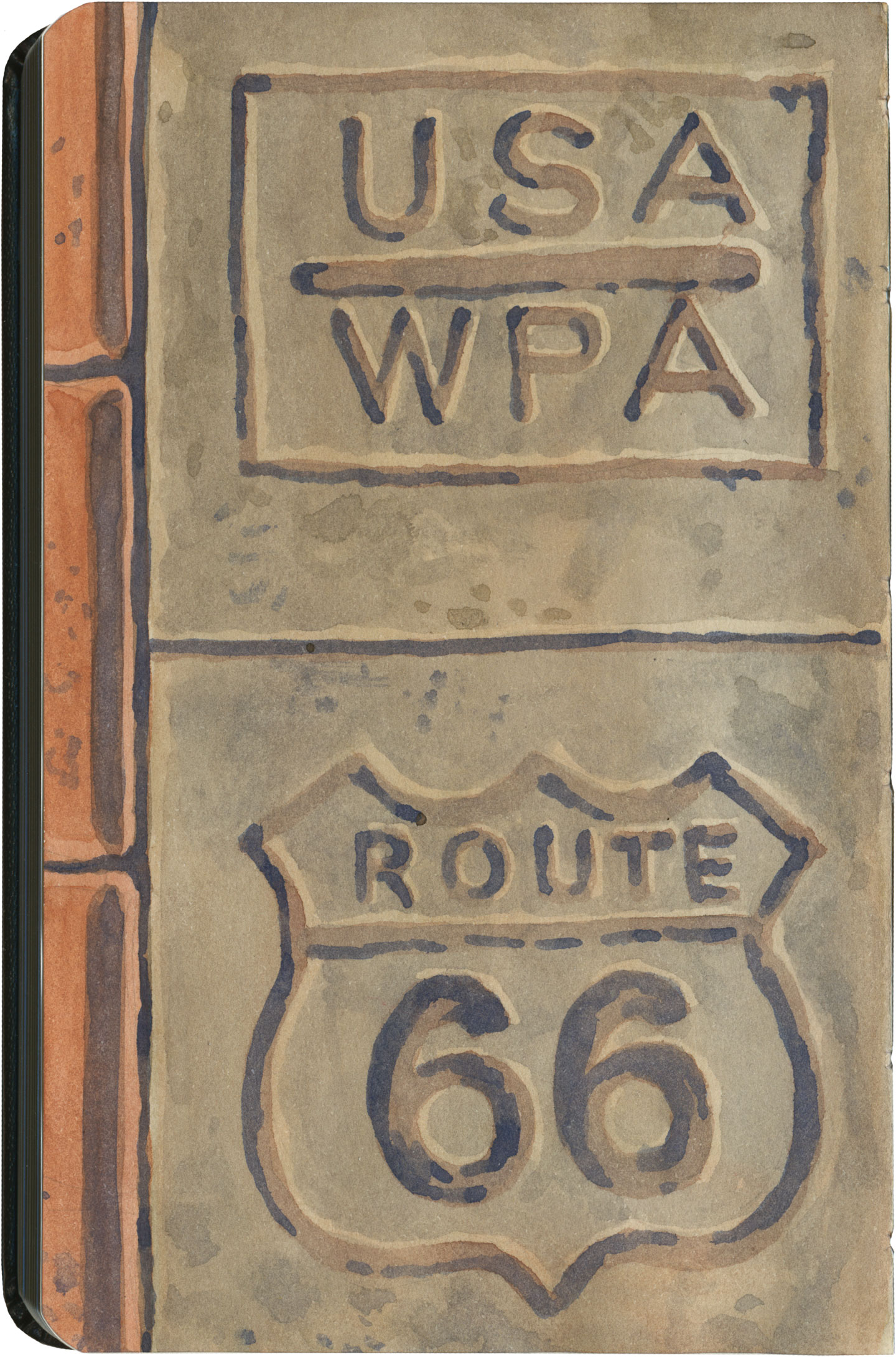

More than anything, I think it’s this constant mixing of things that marks Harvey’s legacy: east and west, Native and Anglo, public and private. (For instance, the hotels and restaurants themselves were funded by the private railroad company, but many of them were located on or near public lands, and many used government-funded labor to build them.) I don’t think Harvey gets much of the credit for it, but the WPA (Works Progress Administration, another Alphabet Soup agency) borrowed heavily from Harvey House ideas and aesthetics when they built the national park lodges in the 1920s and 30s.

And sadly, it’s no wonder: while the national park lodges still stand, protected on public land, very few Harvey Houses survive today, and even fewer are still hotels or restaurants. Many of them were demolished in the 1970s and 80s—an awful time to be an historic building—and still others hold on as empty shells, stripped of all their glory and slowly decaying.

Still, Route 66 is the best path to take to discover what’s left of Fred Harvey’s world. As you drive the Mother Road along the old Santa Fe railway, remember that somebody came before you—leaving the lights on and turning back the covers, all in hopes of making the West feel more welcoming.