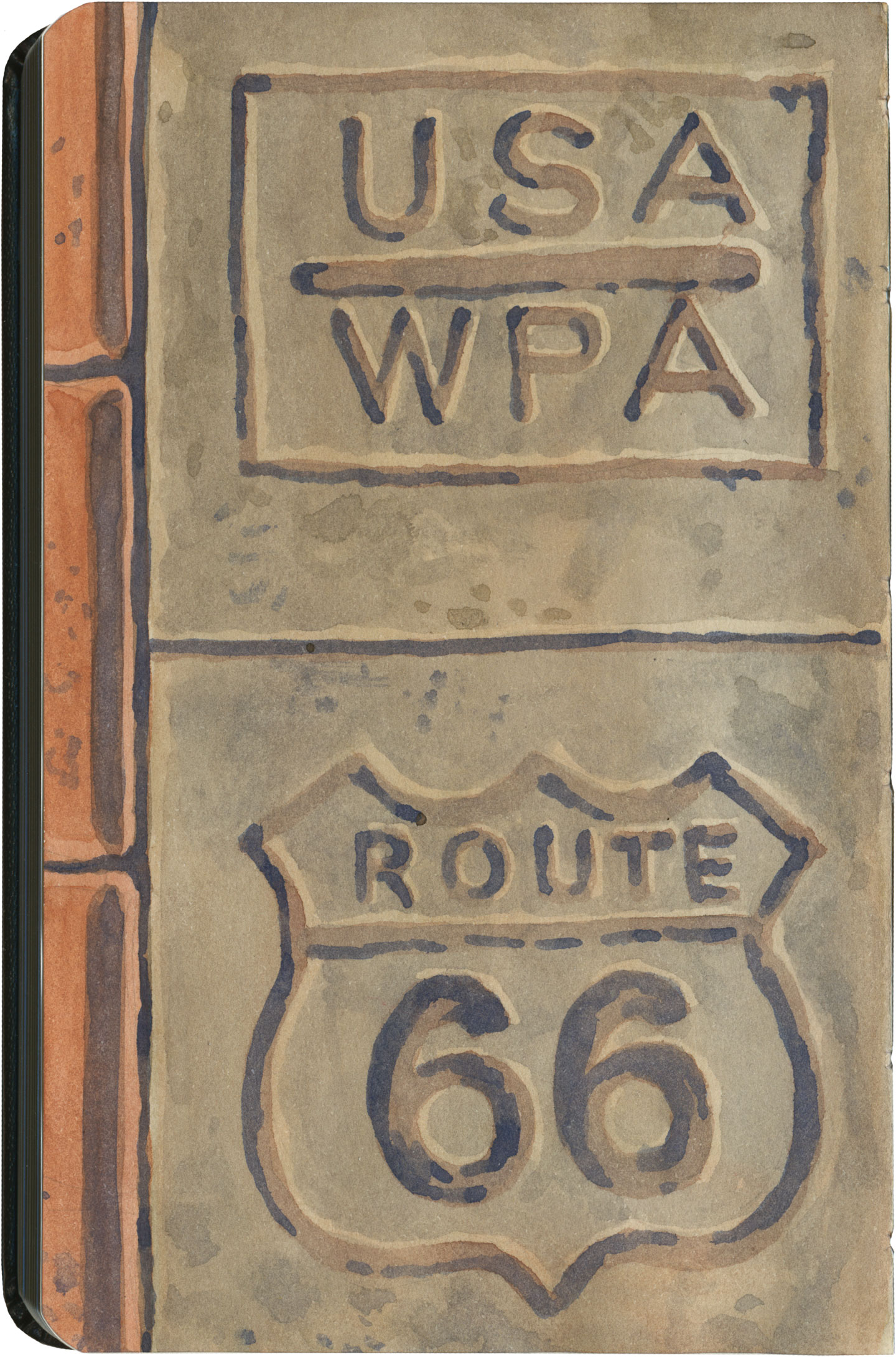

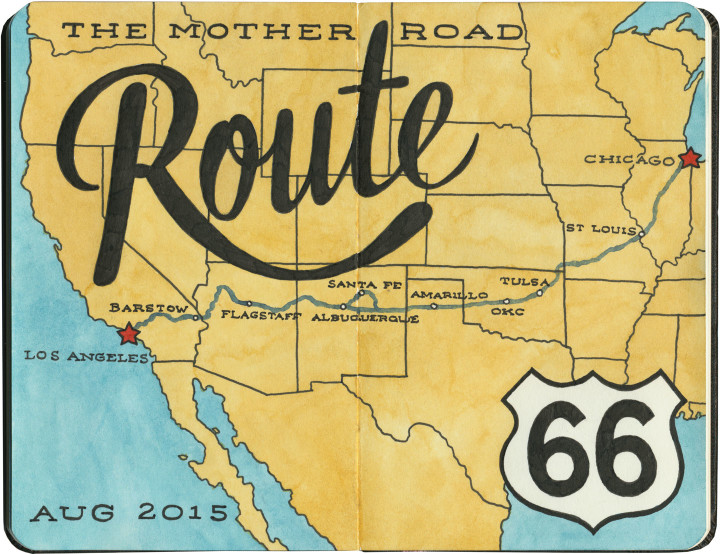

This post is part of an ongoing series called 66 Fridays, which explores the wonders of old Route 66. Click on the preceding “66 Fridays” link to view all posts in the series, or visit the initial overview post here.

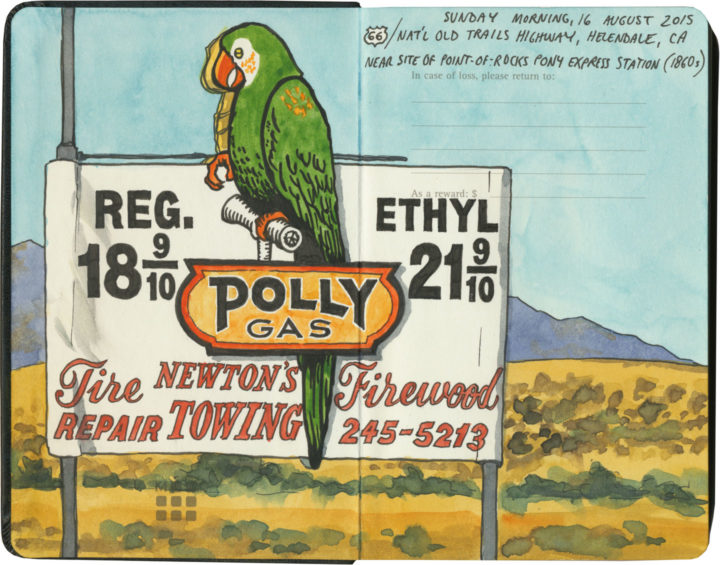

Polly want a pit stop?

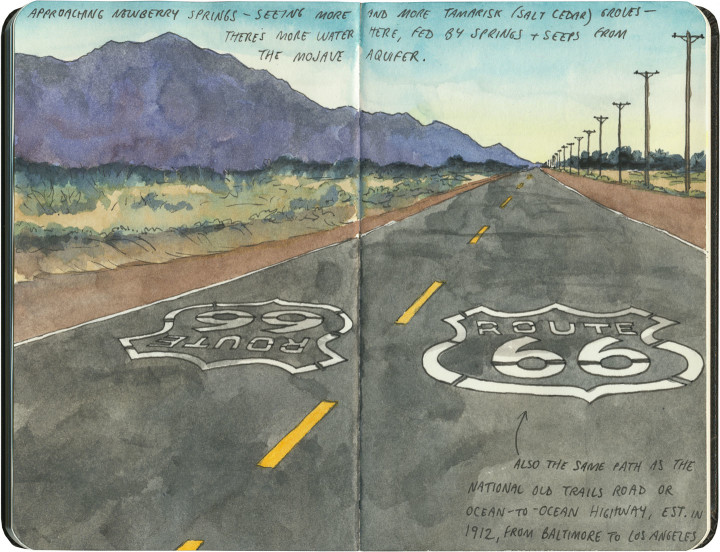

If you’re going to take a road trip, at some point you’re going to need to refuel. And nobody knows how to fill your tank like the folks on Route 66. Of course, since the route crosses a big swath of American oil country, you’ll know that the milk of the Mother Road is petroleum.

Cuba, Missouri

The thing is, though, the designers and architects and advertisers and engineers responsible for putting gas stations all along the route got into the spirit of 66 in their own unique ways. Forget what you know about ugly garages lining Interstate exits—many of Route 66’s filling stations are downright works of art.

Cuba, Missouri

And many of them look absolutely nothing like gas stations.

Interestingly, the Mother Road was built at a time when more and more Americans owned automobiles—all over the country there was an increasingly large demand for petrol. Filling stations moved into town centers and residential neighborhoods, and some oil companies wanted their fuel stops to blend in with the neighborhood architecture.

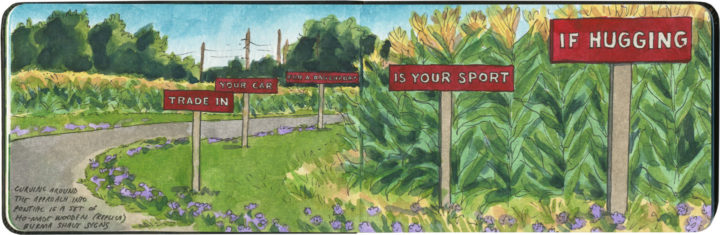

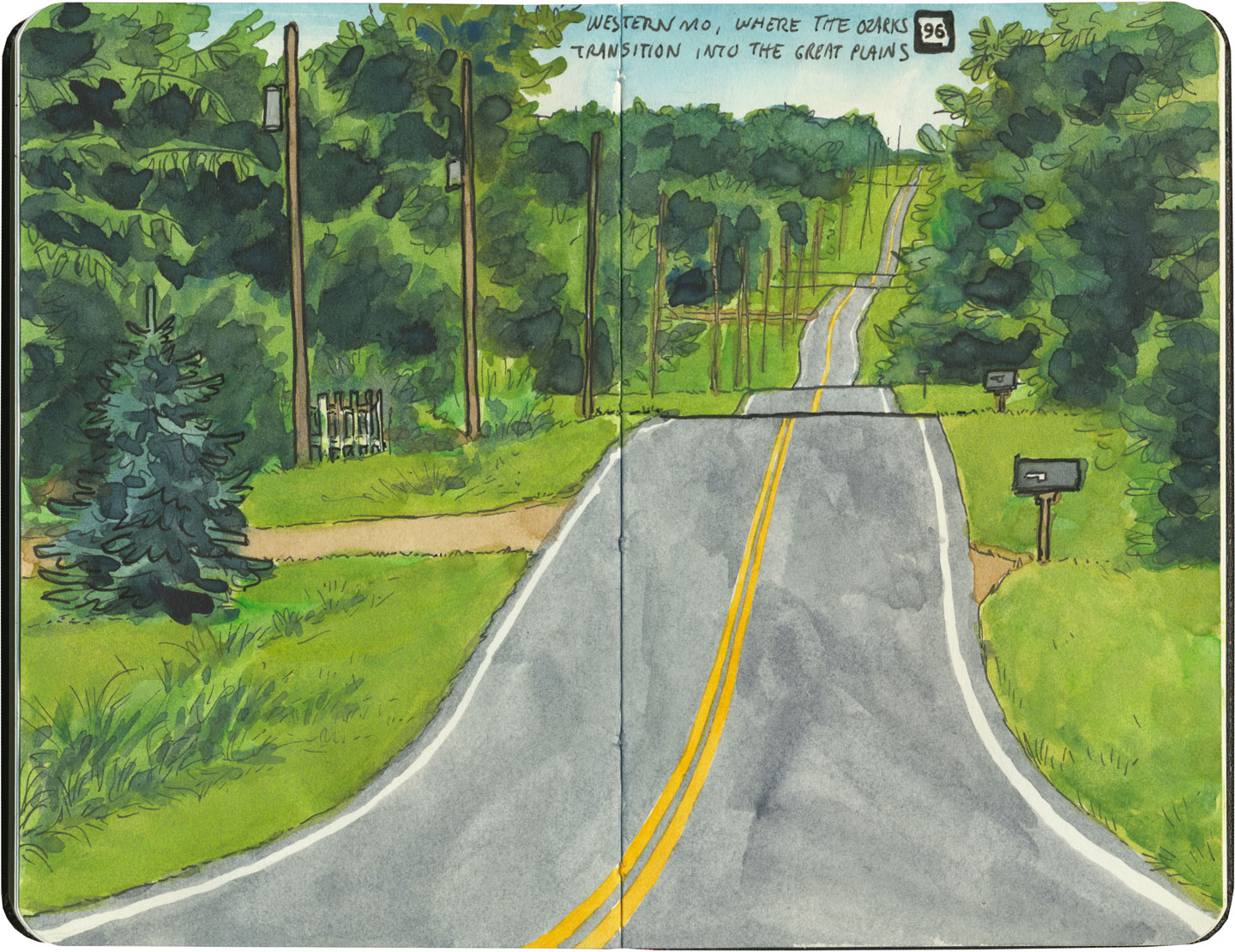

Since American architecture is highly regional in nature, many of these “camoflaged” filling stations took on the look of their local culture—Spanish-Mission-style canopies in California, limestone façades in the Ozarks, clapboard farmhouse lookalikes in the Plains, etc. And then, of course, architectural tastes changed over the years, so you’ll find examples from the Victorian era to midcentury pop-Googie, and everything in between. (Not to mention the tradition of kitschy filling stations shaped like random objects or weird ho-made roadside giants.) Finally, each oil company wanted to attract customers away from the others, so they relied on creating distinctive architectural styles as a form of branding. The result is a veritable encyclopedia of diverse and spectacular specimens—and Route 66 might just have the best collection of all.

Albuquerque, New Mexico

After a few hundred miles, we started getting really good at spotting the buildings that used to be filling stations (this is an obvious one, but many had been deeply camoflaged, or totally remade in some other image, or else fallen into ruin). And we also developed a knack for pegging which style belonged to which company (above is a classic 1930s Texaco design).

Tulsa, Oklahoma

Then again, sometimes a building would throw us completely—the sealed-up garage bays hint at the Blue Dome’s history, but if I didn’t know better, I would have guessed this was once a Greek Orthodox church or something.

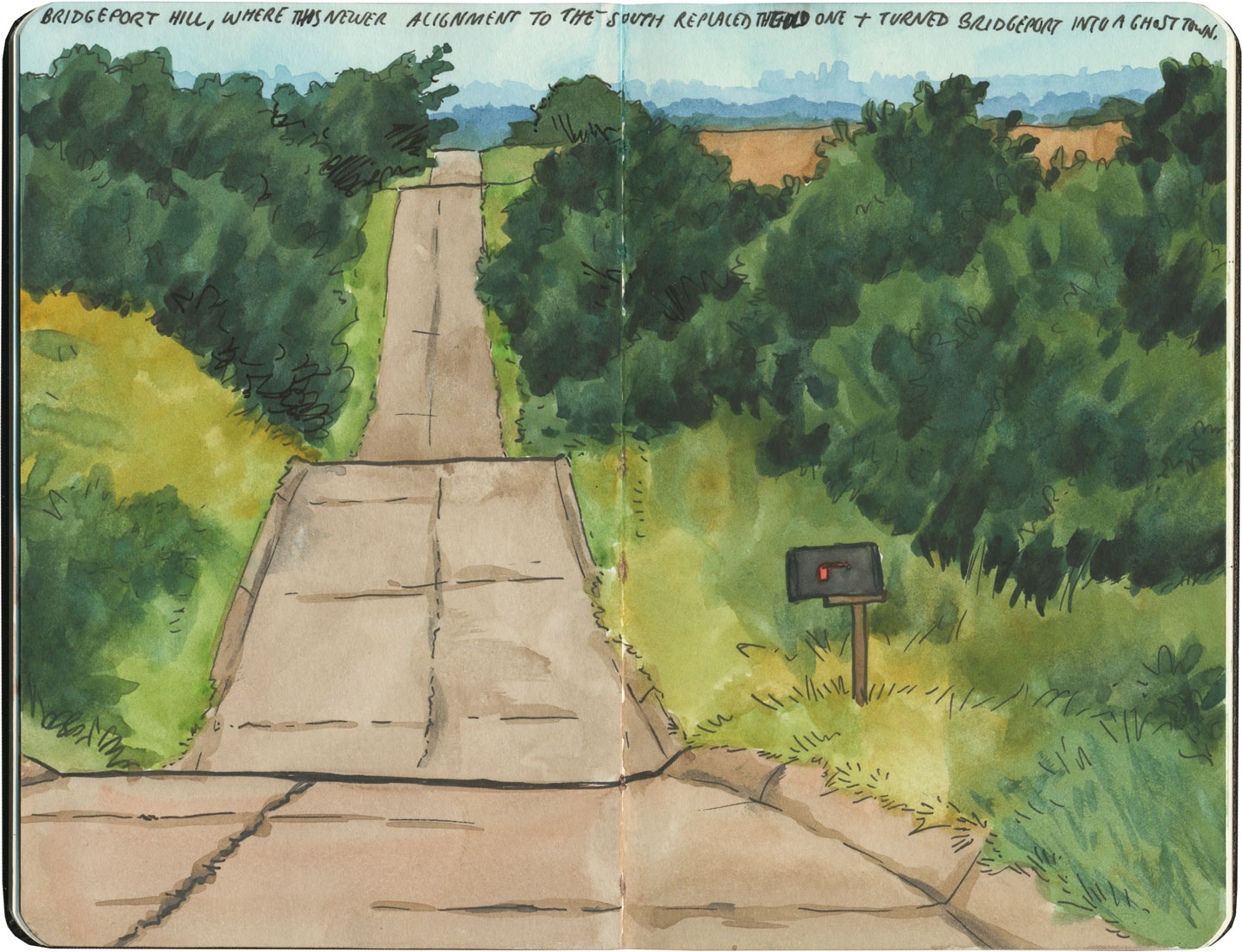

Spencer, Missouri

The filling stations of Route 66 also serve as markers of time’s passage, and the rise and fall of communities along the way. This one is all that remains of a ghost town in Missouri that fell into disuse when the highway changed its route. (I’m not talking about the advent of the Interstate, either, although that’s a common story—this place lost its prime spot decades before that, when the 66 alignment was simply moved to a spot further south.)

Ranco Cucamonga, California

While many petroleum relics have faded into oblivion, others are being brought back, at least in some form or other. Above is one of the oldest specimens we found (it actually predates the birth of Route 66 by nearly a decade). While part of the structure has been torn down, at least the main part of the station is getting a lovely facelift.

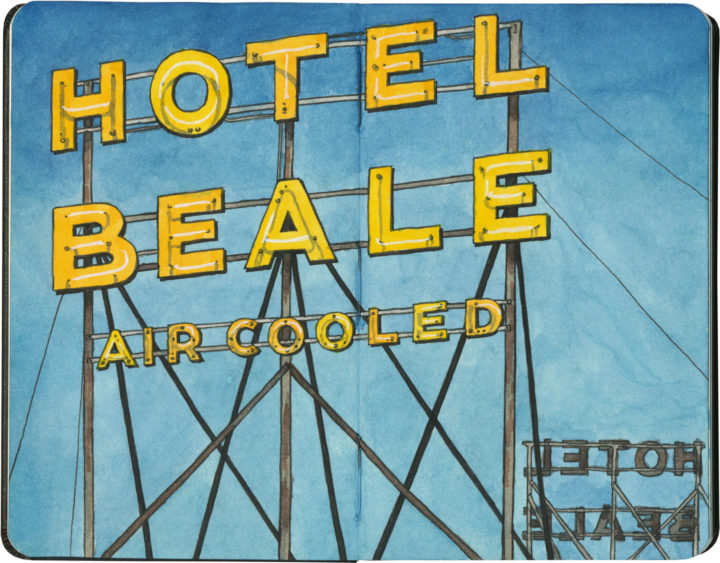

Needles, California

It’s not just the oldest samples being preserved, either. This guy is only a little over fifty years old, but it, too, has been returned to its former glory.

Normal, Illinois

For many old stations, however, the opposite is true. Countless specimens either sit empty, their original purpose unknown to the average passerby—or else they get cannibalized and transformed into some other creature, usually without any fanfare.

Hydro, Oklahoma

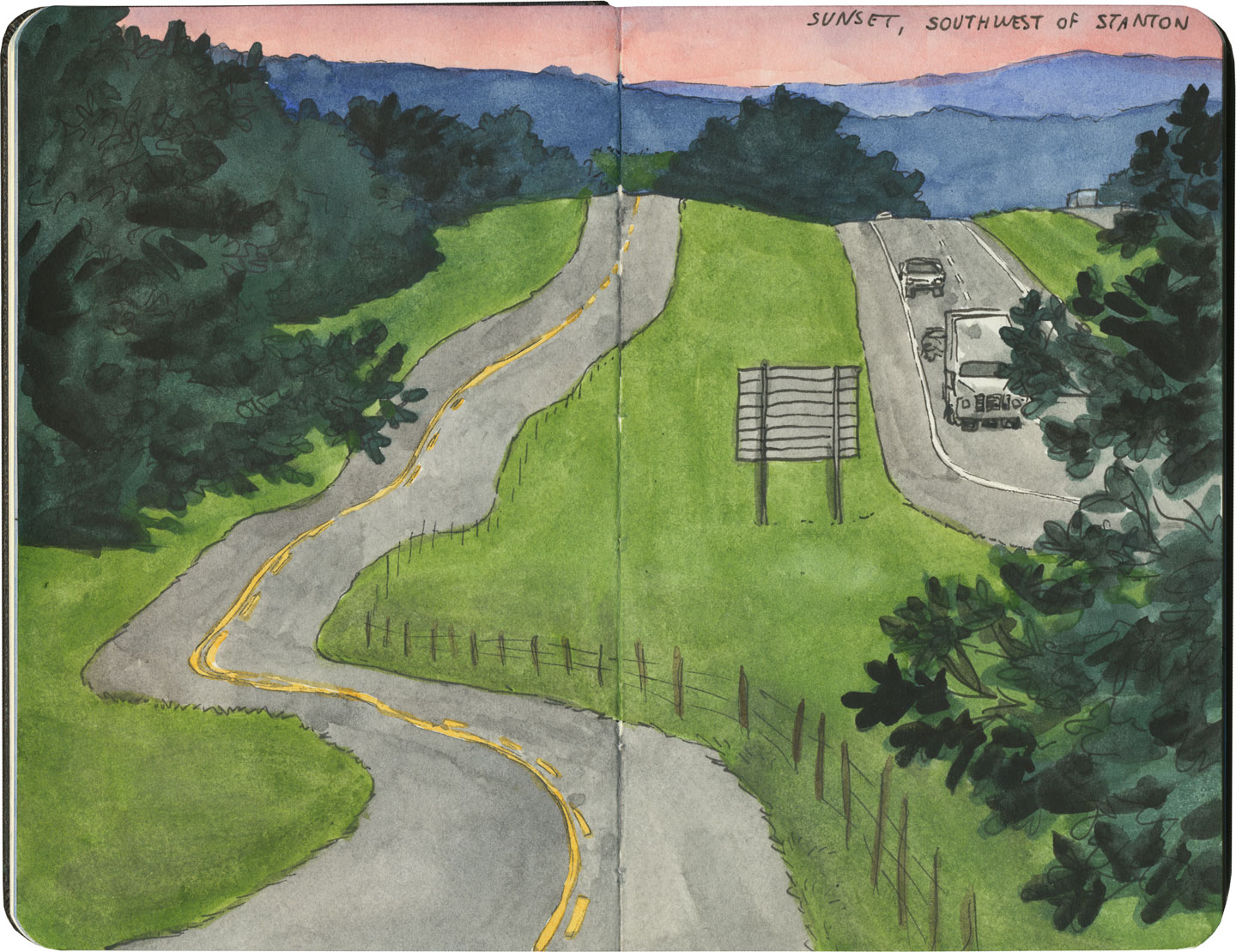

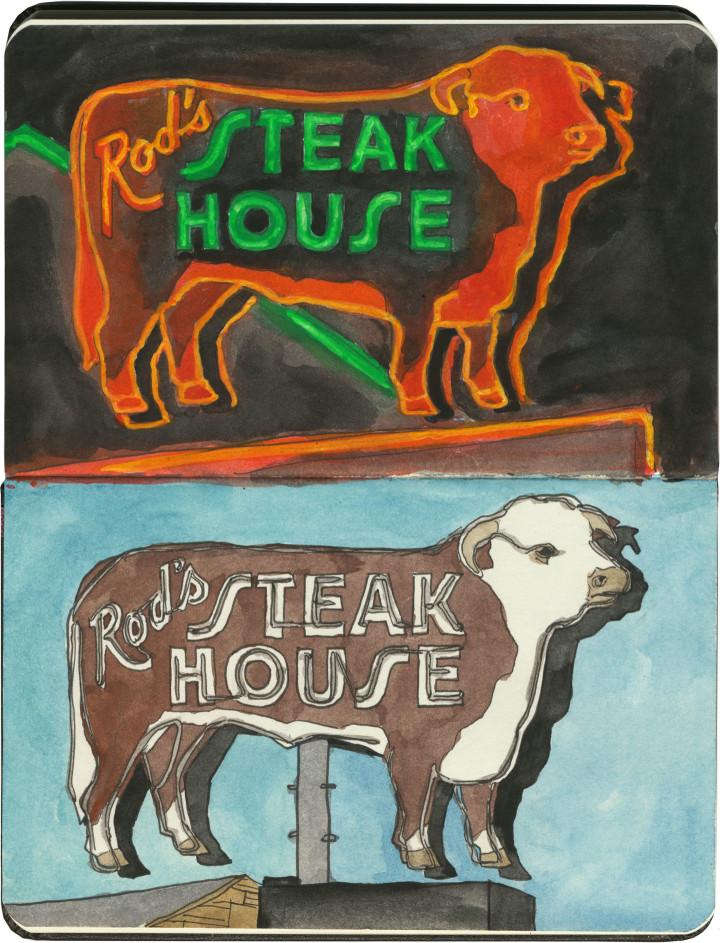

These stories of disrepair and restoration interest me greatly, of course, but what really gets me is the story of each place: the whys and wherefores of each station, and the tastes and quirks of the people who either built or ran them.

Cool Springs, Arizona

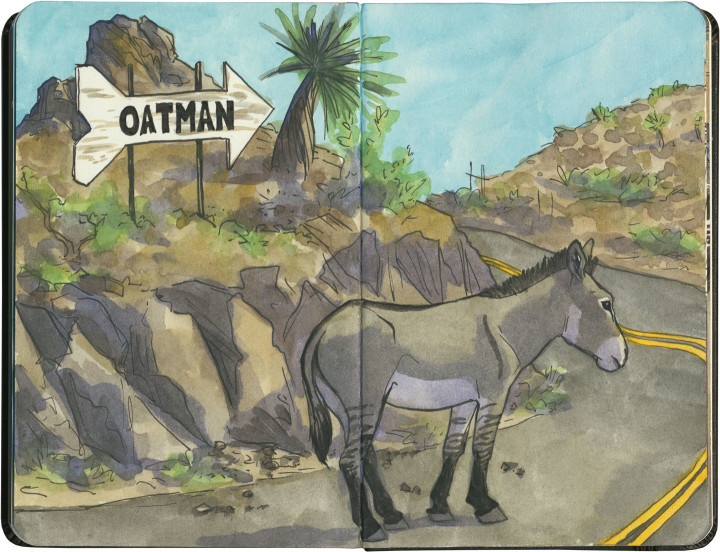

After all, Route 66 crosses through some seriously unpopulated territory. Many of these old filling stations were the only game in town—or in the most remote corners, something closer to the last chance for salvation.

Commerce, Oklahoma

While others, meanwhile, live on in notoriety, attracting tourists to the spots where blood was shed or infamous characters once stood.

Odell, Illinois

Still, most tell the story of perfectly ordinary people running perfectly ordinary businesses along one of the backbones of American travel and commerce. They might be extraordinary today, but usually that’s boils down to having somehow lasted long enough to stand out amongst more modern surroundings.

Shamrock, Texas

I’m glad, at least, that I’m obviously not the only one who has noticed these things—that there is an army of conservators and historians and artists and boosters out there, preserving as many of these old filling stations as possible, and documenting the ones that can’t be saved.

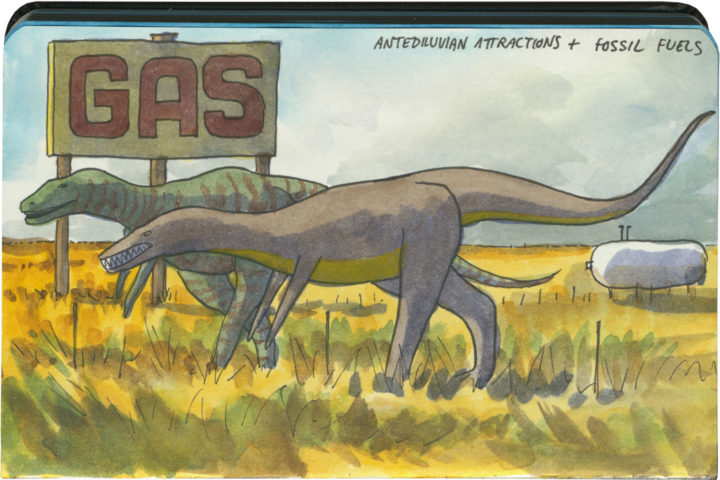

I know that these days, oil companies have fallen out of public favor (heaven knows I have my own beef with the oil industry)—regardless of their nostalgia, these places are also reminders of American excess and the damaging effects of fossil fuels. Yet however we may be careening toward Peak Oil, these relics still have a place on the Mother Road—the path that might just traverse this country’s Peak History.