This post is part of an ongoing series called 66 Fridays, which explores the wonders of old Route 66. Click on the preceding “66 Fridays” link to view all posts in the series, or visit the initial overview post here.

One of the grandest Route 66 traditions is the souvenir shop—or as it is more frequently named here, the trading post. And few Mother Road icons have such a long history. Starting as supply hubs and early post offices for fur traders, wagon trains, survey expeditions, gold prospectors and the like, trading posts were bastions of commerce and news in remote places.

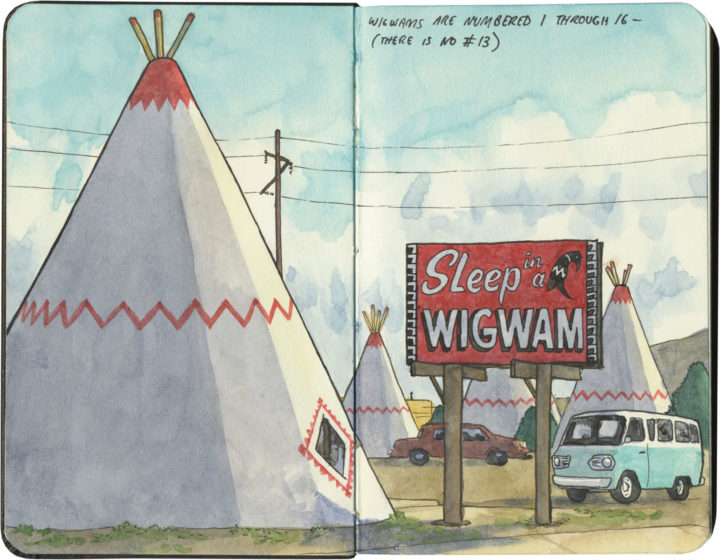

The contemporary version of the trading post has sprung out of twentieth-century myths of the Old West: modern tourists wanted to experience a slice of the Pony Express, or send postcards from Boot Hill, or bring home a piece of Navajo jewelry—in air-conditioned comfort, of course.

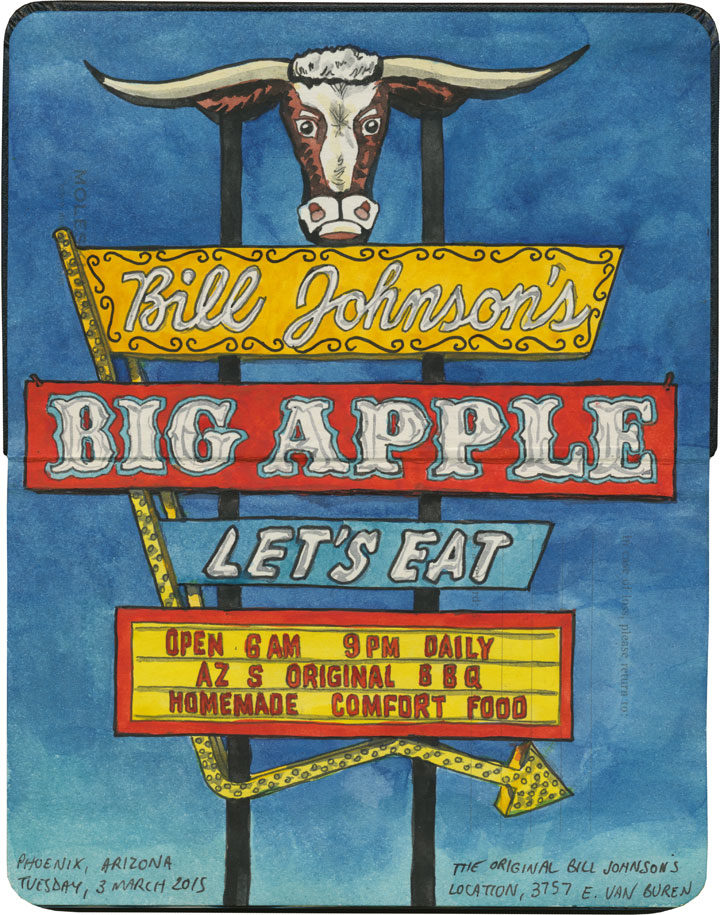

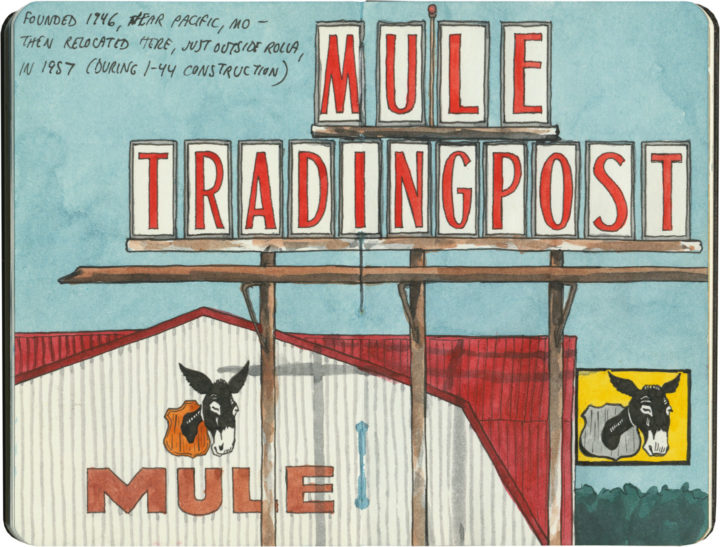

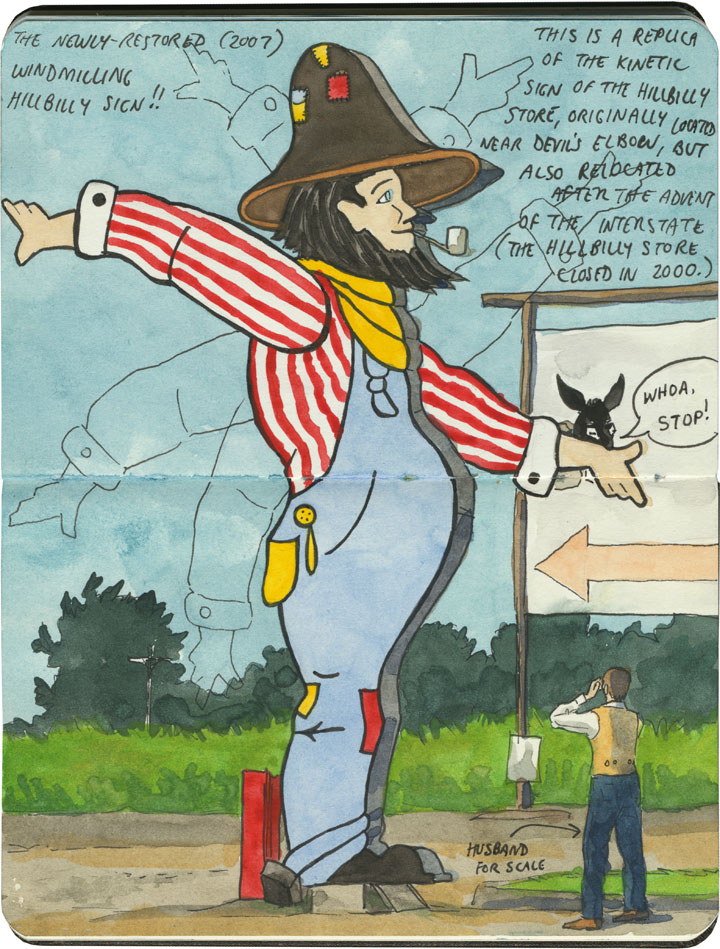

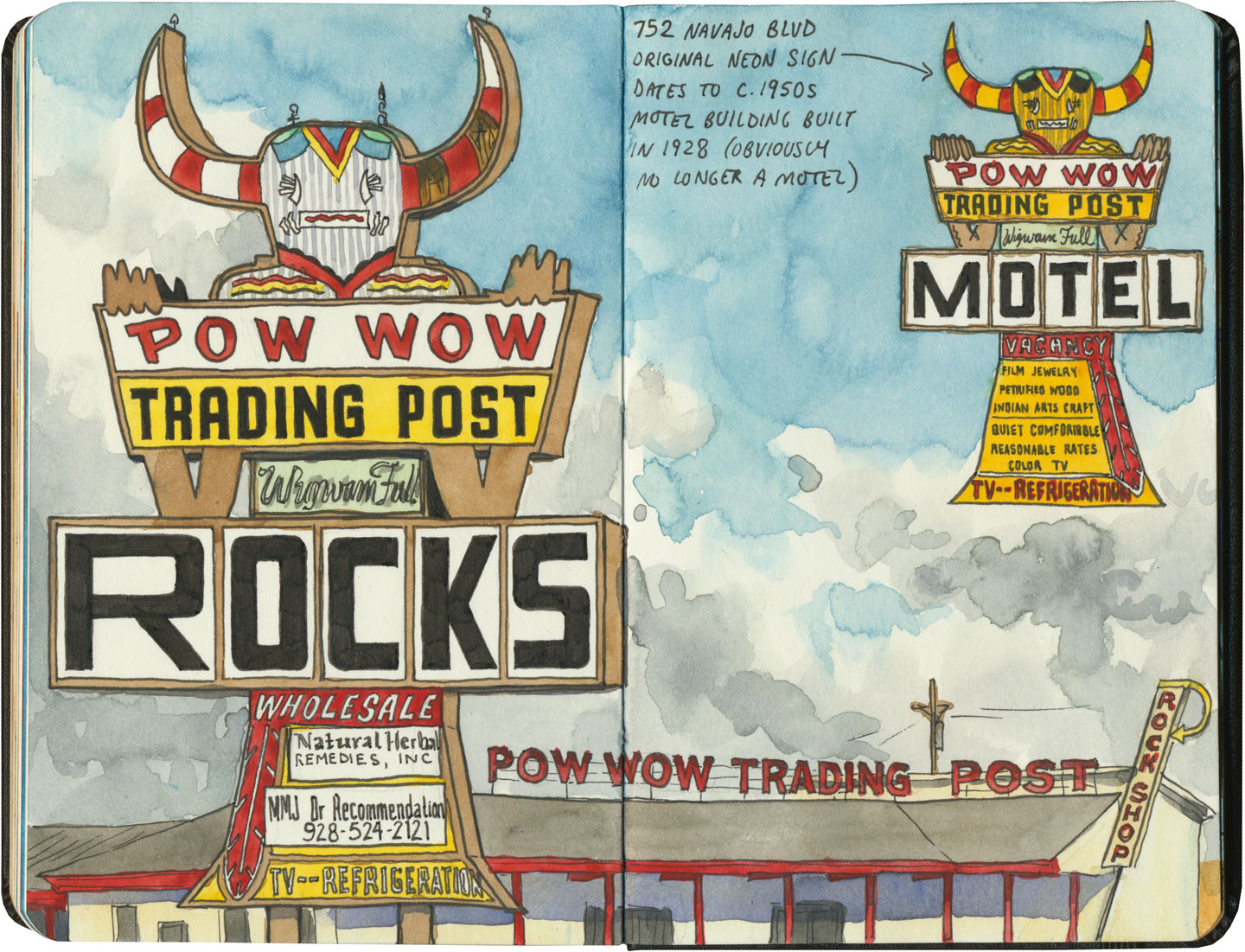

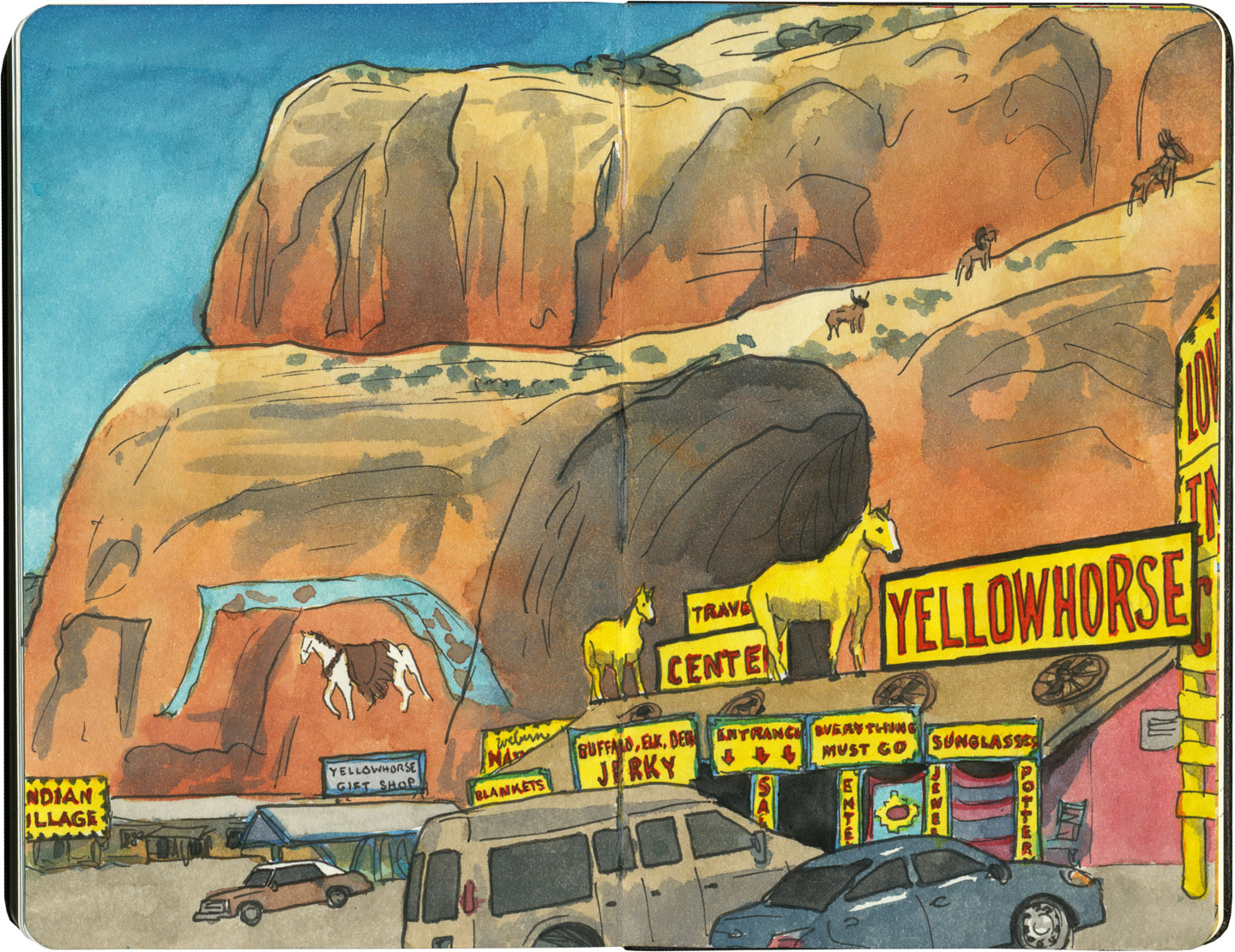

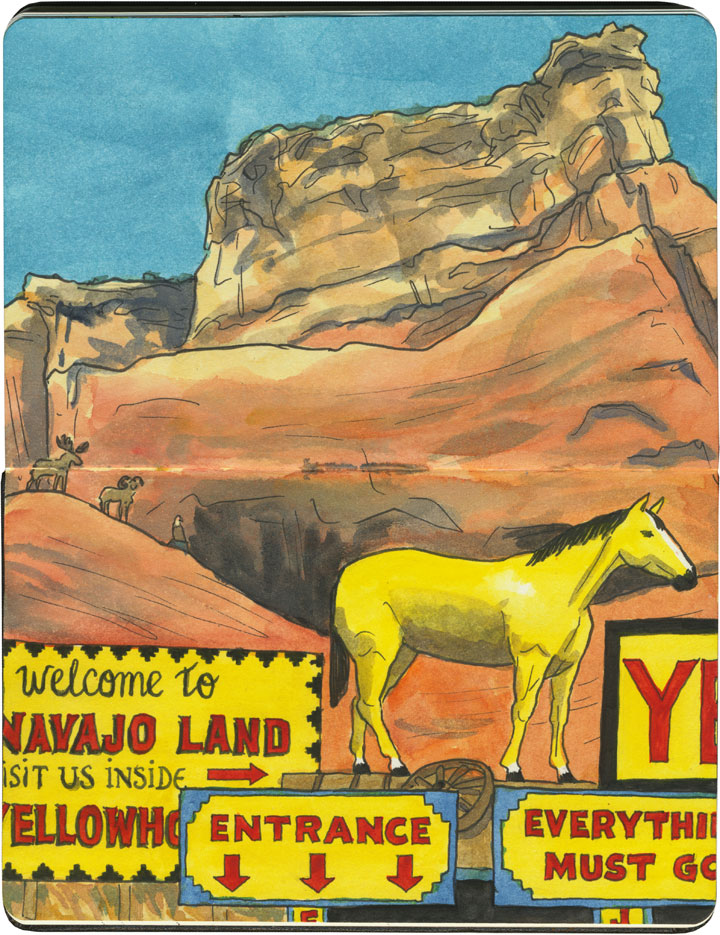

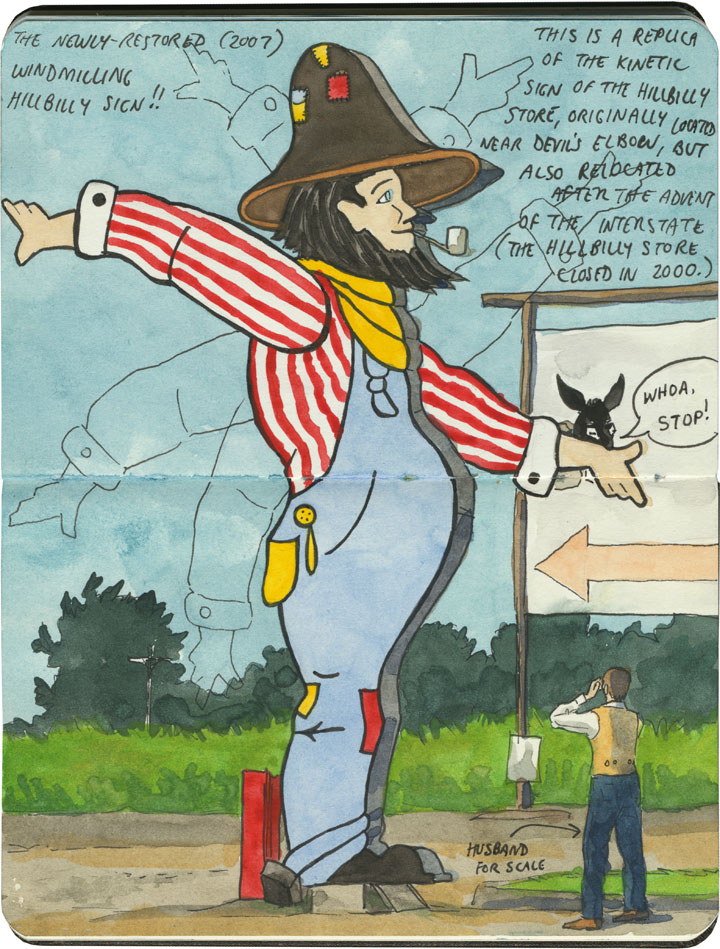

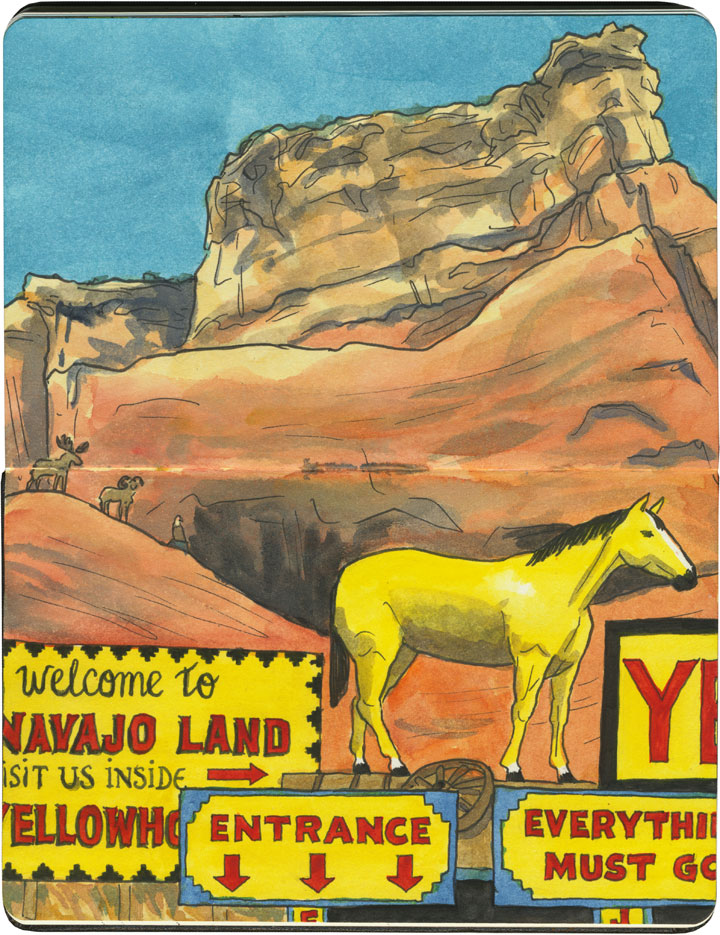

And nobody has cashed in on trading posts quite like Route 66: the Jackrabbit, the Continental Divide, Tee Pee Curios, the list goes on. On the Mother Road, the term “trading post” has become synonymous with “tourist trap”—many of these places combine commerce, entertainment and the flavor of the Wild West (or in the case above, the Hillbilly Ozarks). Far beyond a simple pit stop or junk store, some have more in common with theme parks.

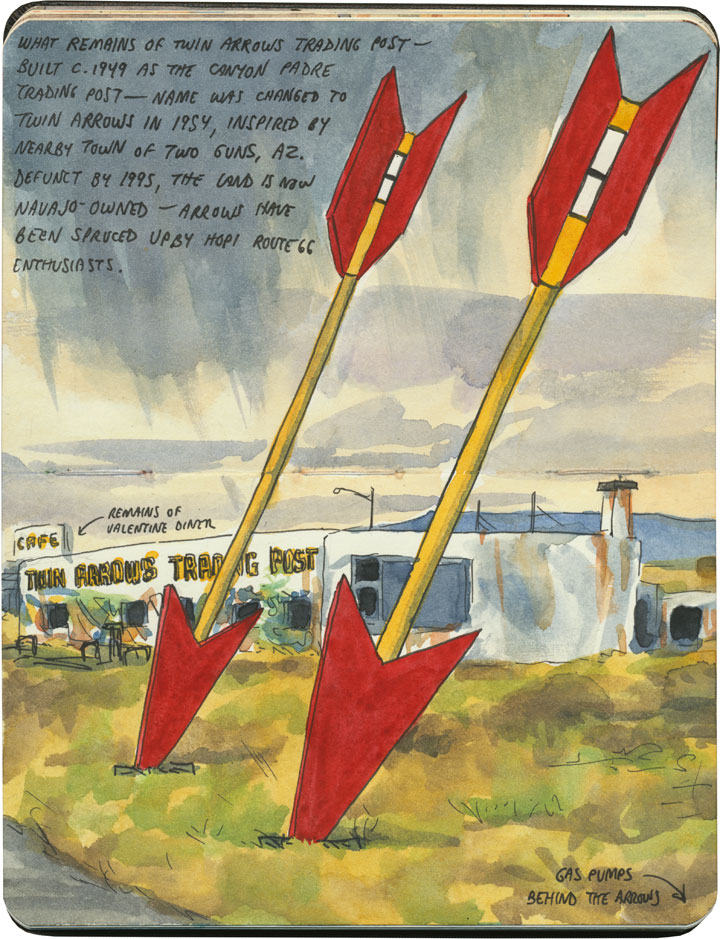

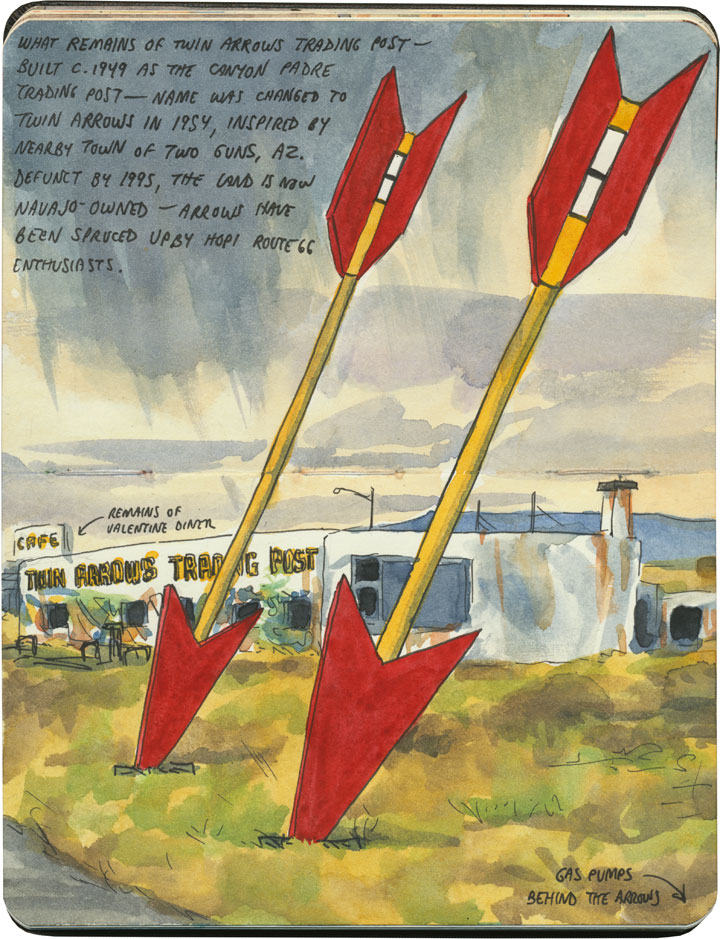

And while some have their roots in the actual Old West, many of these pit stops were built after Route 66 was run through. (Subsequently, in places where the modern Interstate diverted traffic away from 66, many of these trading posts are crumbling or closed altogether.)

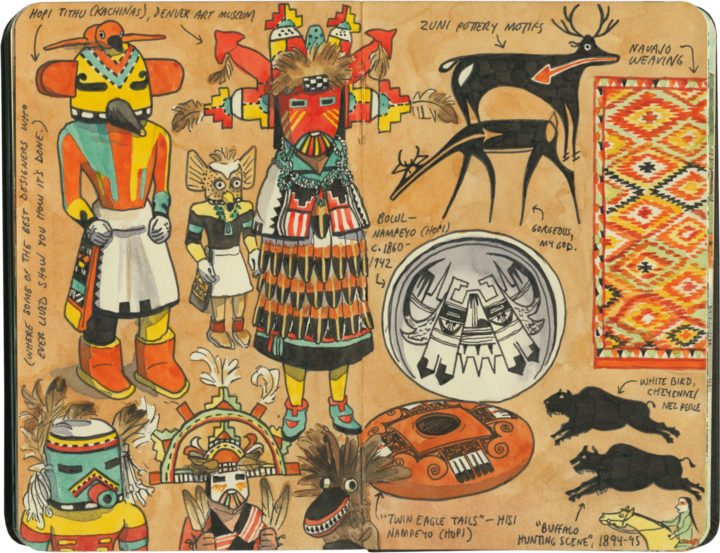

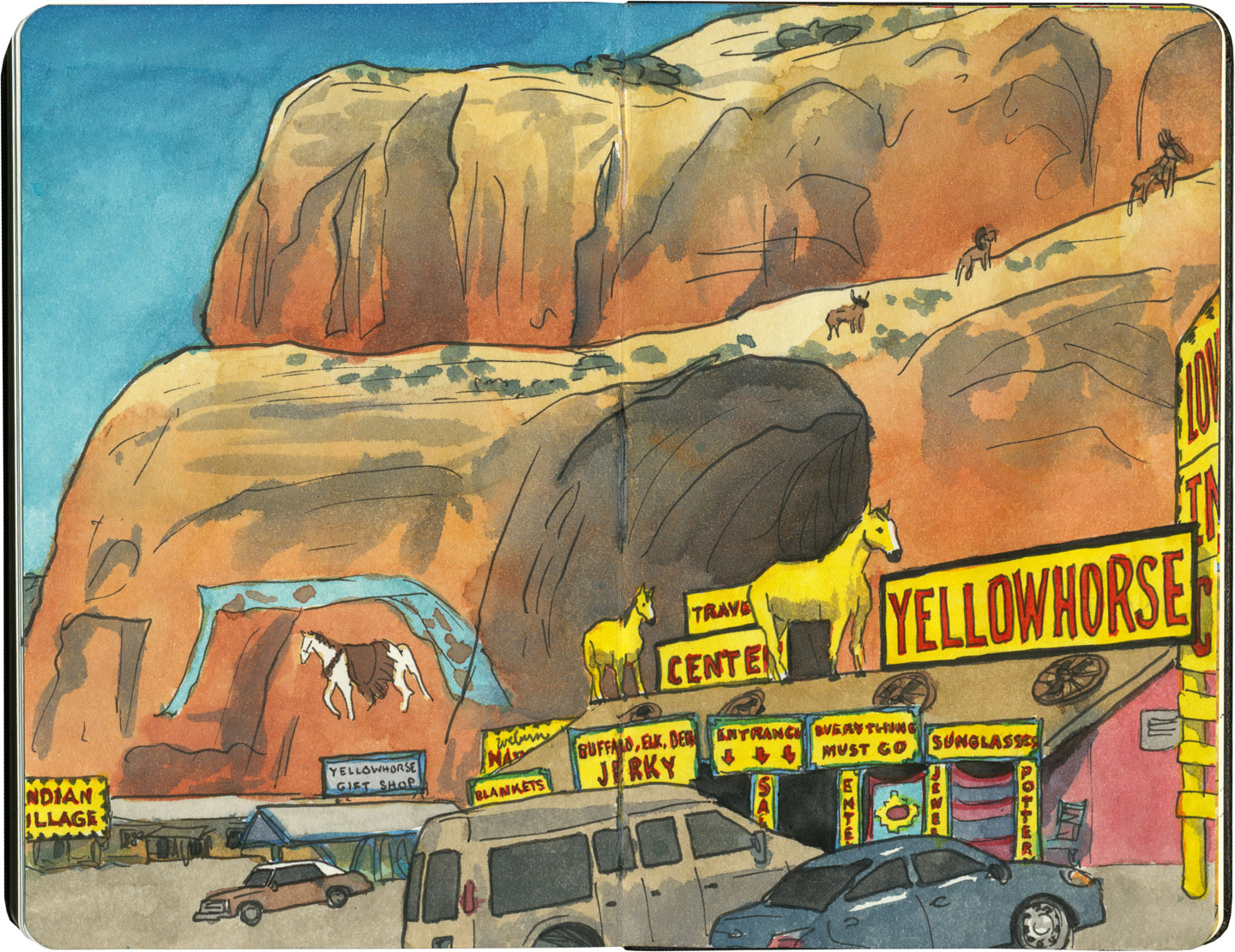

Thanks to historical examples like Hudson’s Bay Company, or the Hubbell Trading Post on the Navajo Nation, which has operated on the pawn (barter) system since the 1870s, we tend to associate trading posts with Indian Country. Route 66 is a prime example: half of the route (over 1300 miles) crosses through Native America, connecting more than 25 Indigenous nations. And since the vast majority of the Mother Road’s trading posts (and nearly all of those west of the Texas-New Mexico line) deal in Native goods, it’s no wonder a road trip through the Southwest makes us think of kachinas and beadwork.

Though many of these shops are run by white owners, some are owned and operated by tribal members themselves.

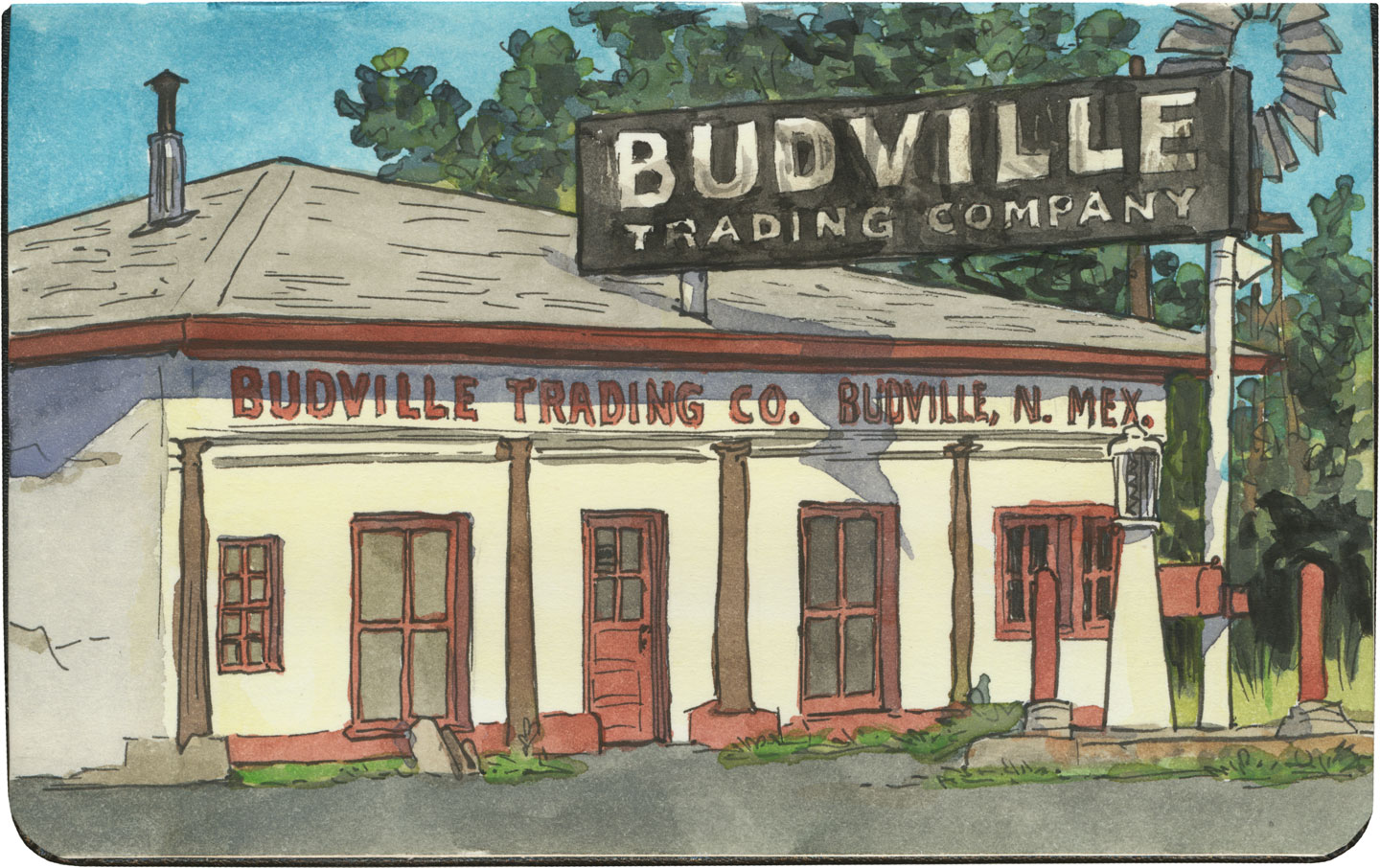

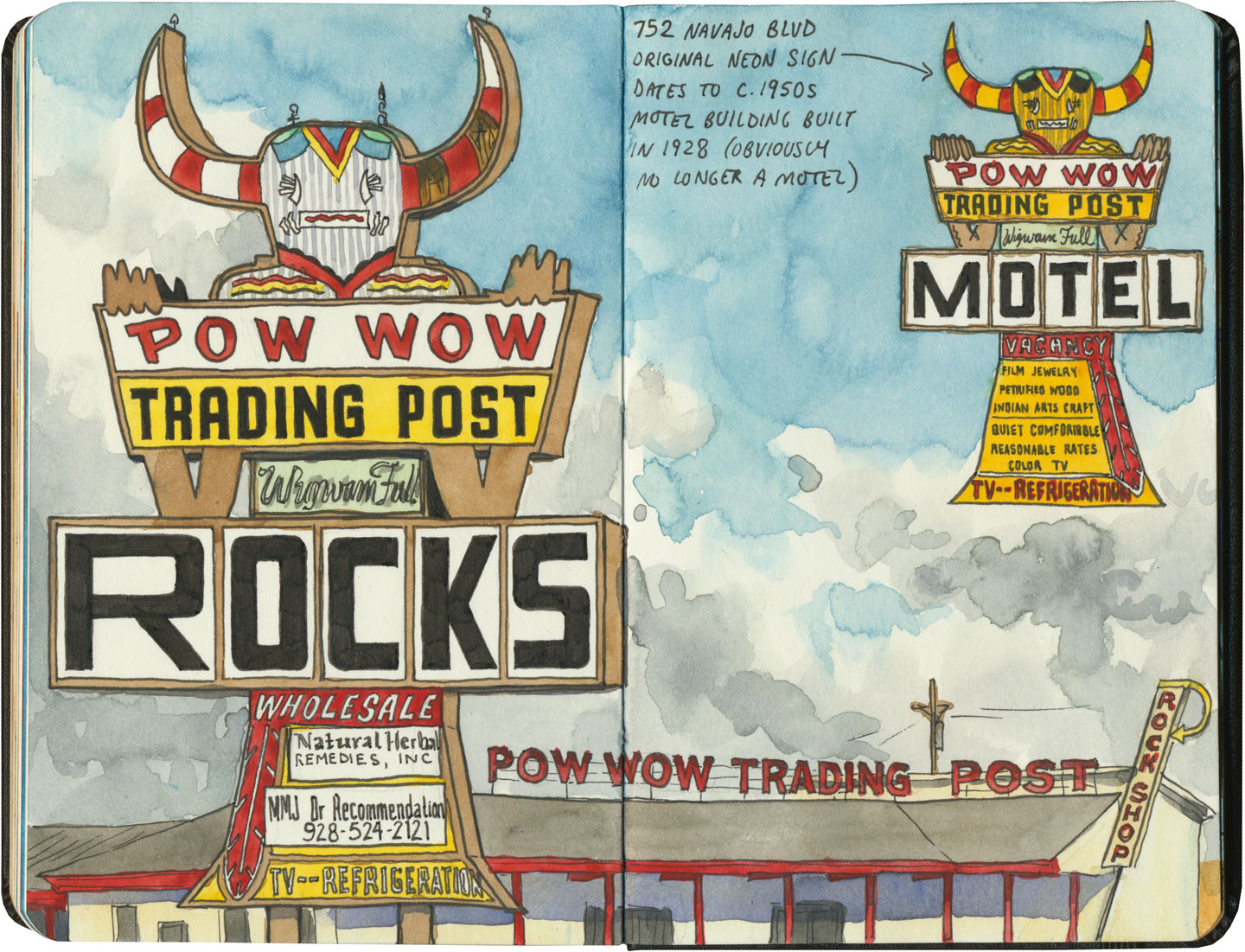

Regardless of who owns them, the overall effect of these places can run the gamut between eye-frying…

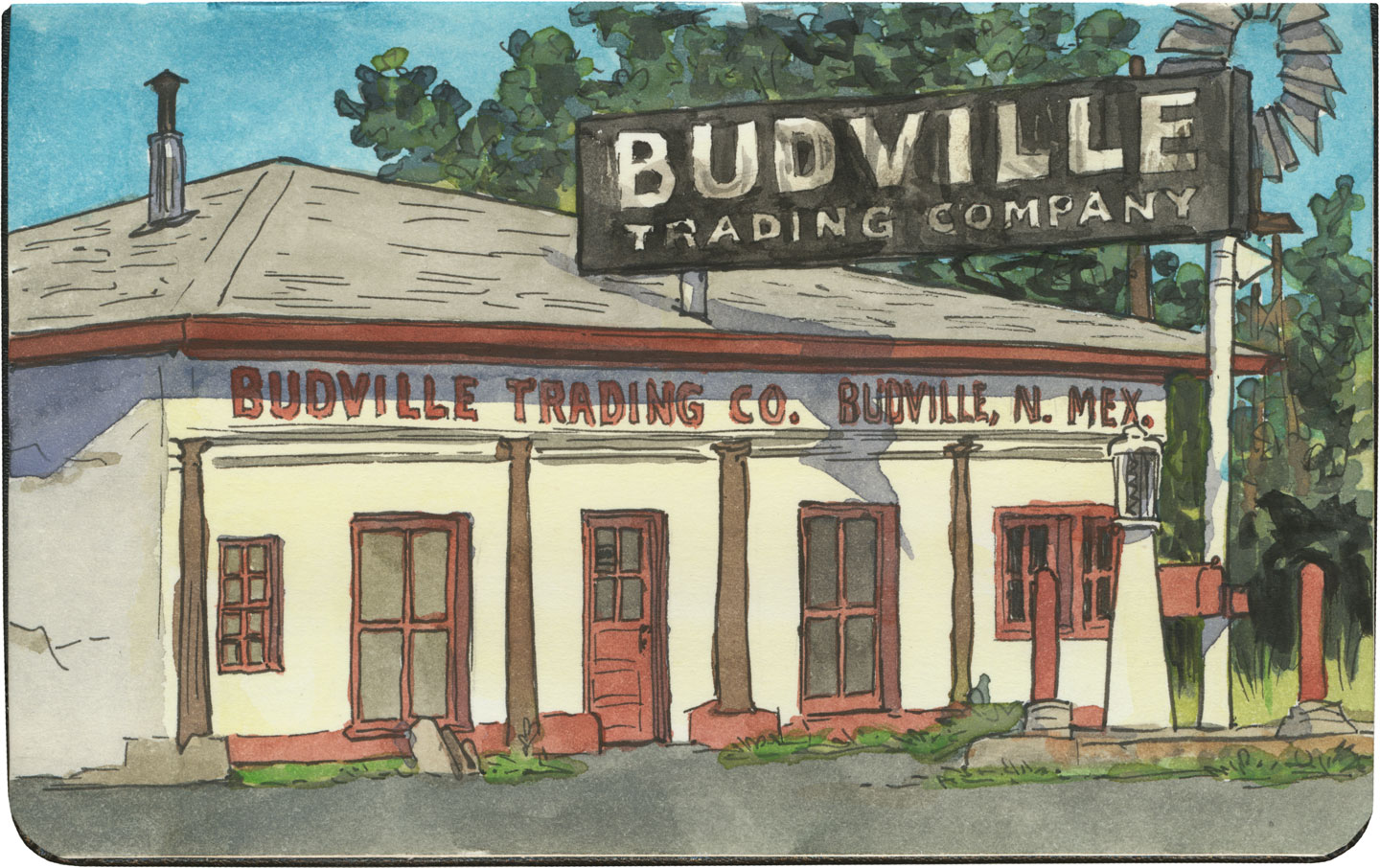

…and downright melancholy.

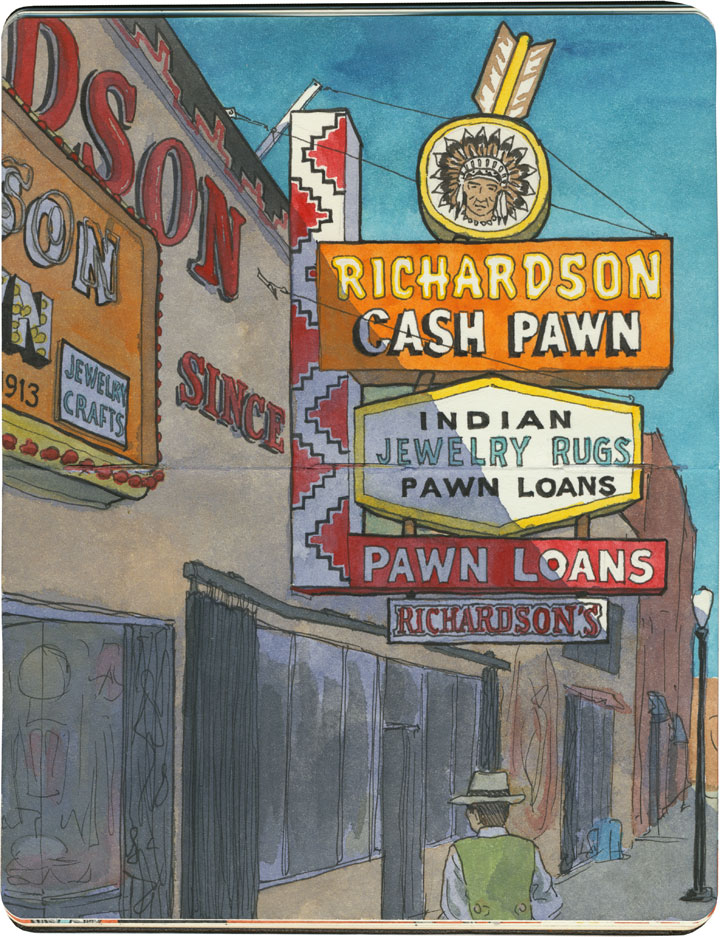

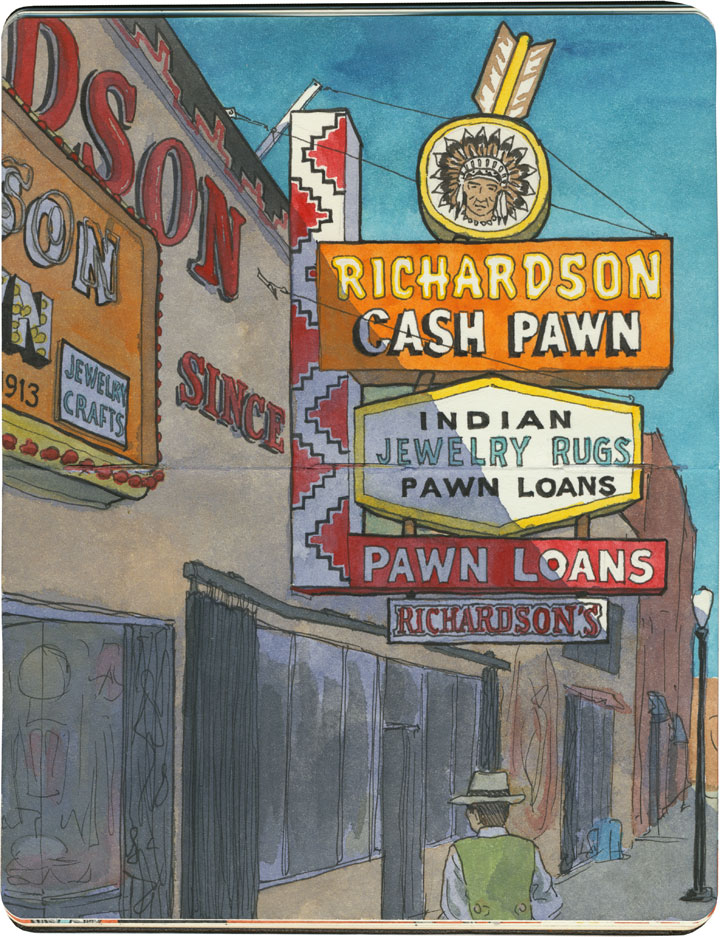

Gallup, New Mexico, has a little of both. Known as the “capital” of Indian Country, the town of 20,000 or so is the gateway to many American Indian nations, home to nearly a quarter of a million Indigenous people. As a result, Gallup is chock-a-block with trading posts and pawn shops, where local Navajo, Hopi, Zuni and others pawn their jewelry and other handmade goods in exchange for cash, staples or dry goods—and the shop owners then sell the jewelry to tourists. Nearly all of these shops are run either by white or, increasingly, Middle-Eastern owners.

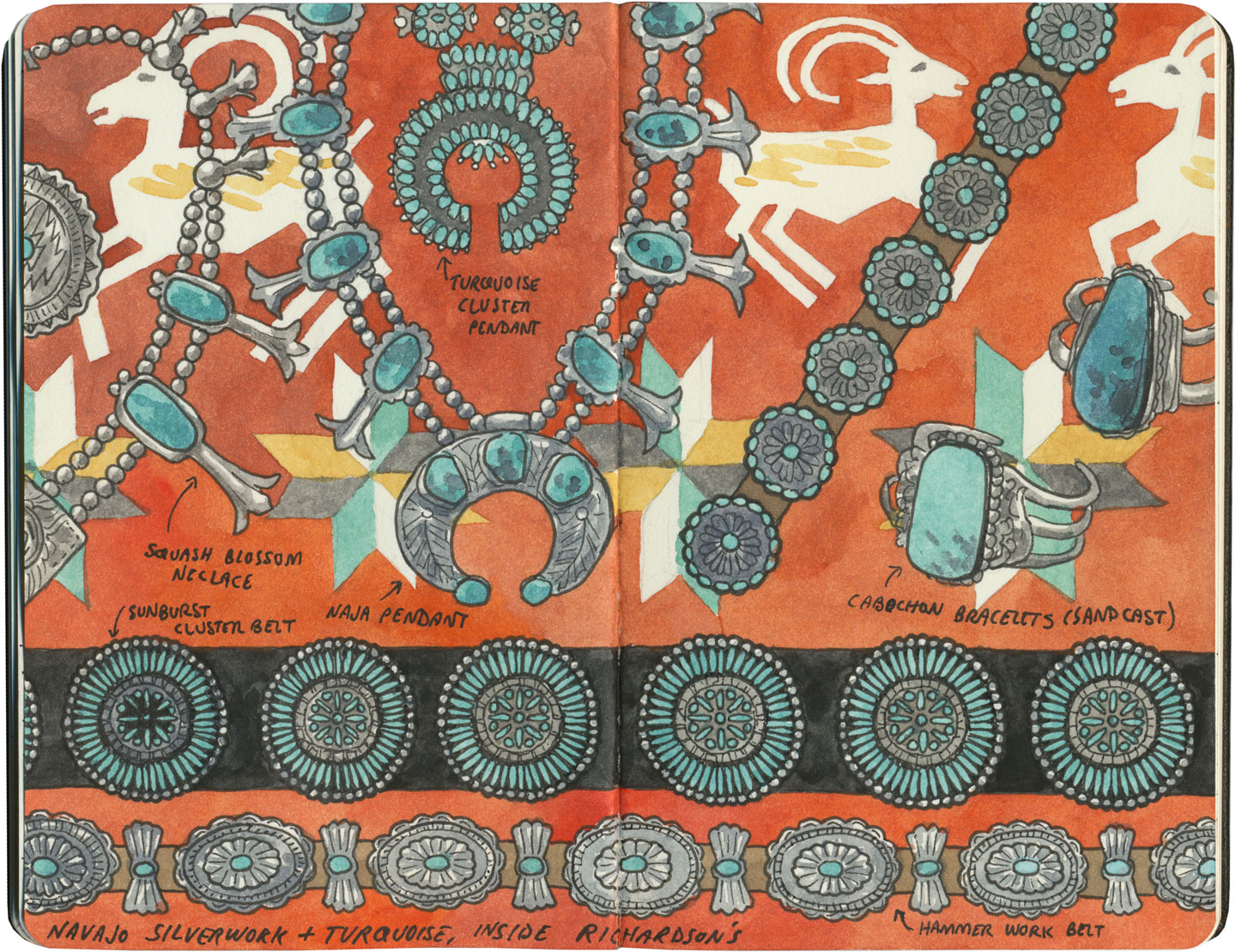

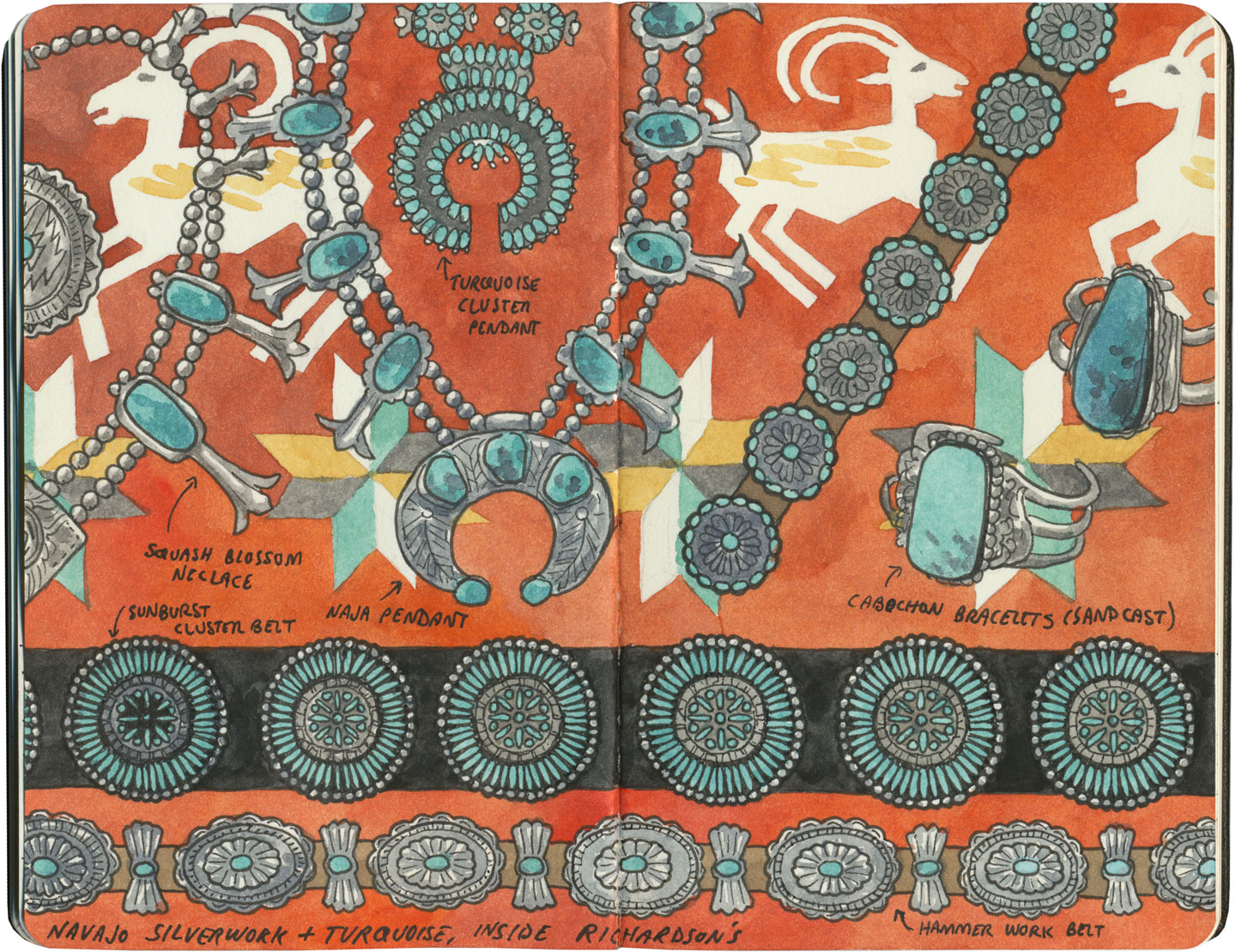

Gallup’s pawn shops have a controversial history, with some establishments accused of dealing in fake goods or cheating Indigenous makers out of a fair price for their work. So I did a little homework before we arrived, and chose Richardson’s as the place we’d visit. The shop has been in operation for over a hundred years, and though the Richardson family is white, they have a long reputation of being reputable dealers with a good relationship with the nations it represents. We marveled at the beauty on display there—some of the jewelry were incredible “old pawn” antique pieces.

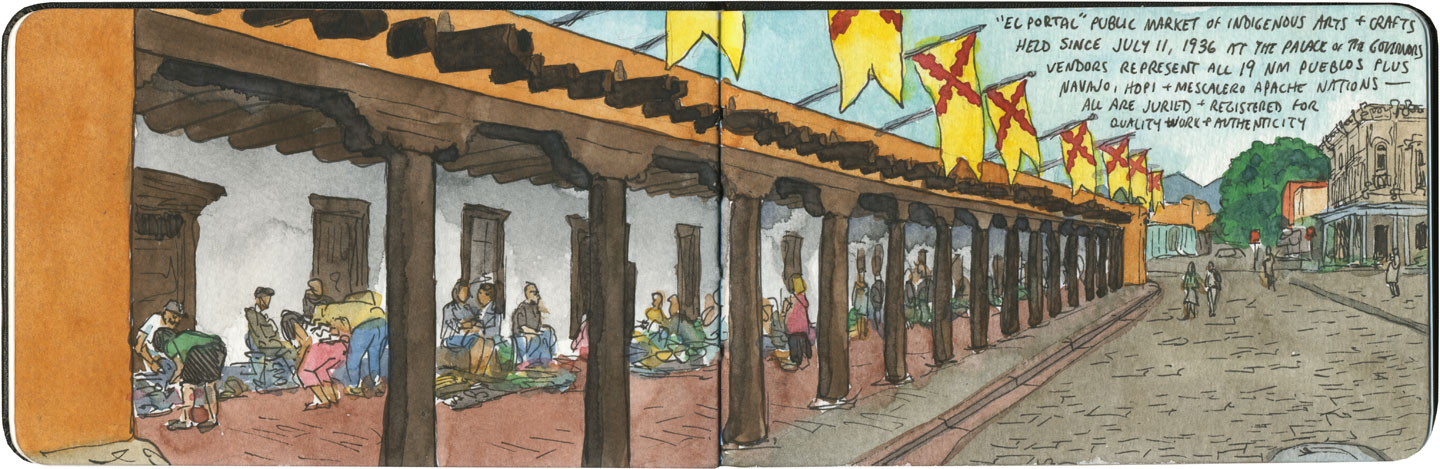

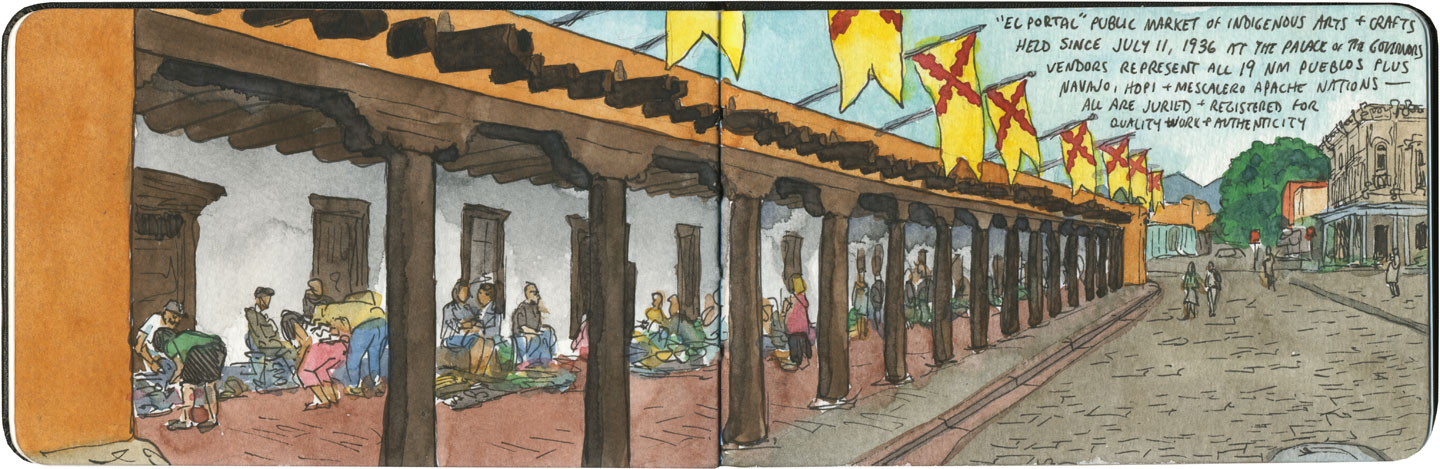

Still, my favorite trading experience on our Route 66 trip was when we had the chance to buy goods directly from the makers. In Santa Fe we shopped at the famous market at the Palace of the Governors, where artisans representing all of the region’s Indigenous cultures sell handmade jewelry, pottery, textiles, etc. at fair-trade prices. Each artist has to apply to the Native American Vendors Program to be included in the market, and the museum at the Palace of the Governors monitors each vendor to make sure the goods are authentic and the prices fair to the makers. (And bonus for history nerds like me: it’s really something to know you’re standing in the oldest continually-occupied public building in the country while you’re at it.)

In the end, I could only afford a couple of small items, but I was happy to know I was paying what they were actually worth (I don’t haggle, especially not with fellow artists), and that the proceeds would go directly to the maker. And best of all, I got to hear the stories behind each piece, from the person who made it.

That seems like a fair trade to me.

Save