This is the fourteenth installment of my Mission Mondays series, exploring all 21 Spanish Missions along the California coast. You can read more about this series, and see a sketch map of all the missions, at this post.

I had some technical difficulties with the site this week, so Mission Monday couldn’t happen on Monday—but everything’s back up and running now, and anyway, isn’t better when Monday turns out to be Friday anyway? So let’s get back to it!

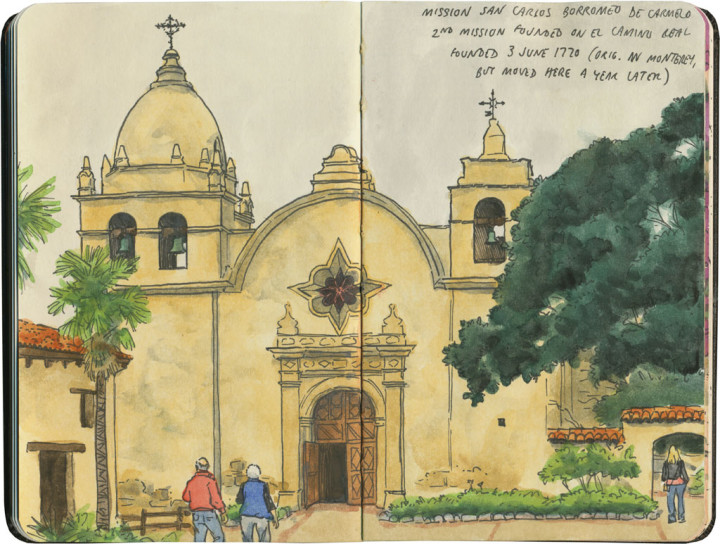

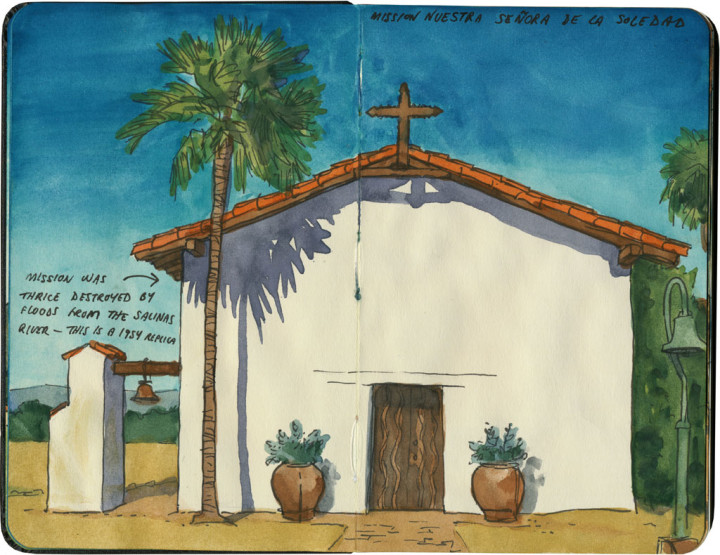

Mission San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo (Carmel Mission for short) is the exact opposite of its nearest neighbor, La Soledad. It’s in the center of town, rather than way out in the country. The structure is mostly original, instead of a rebuilt replica. The complex is ornate and unusual, in contrast to the simple, almost stereotypical style of La Soledad. And while La Soledad is nearly forgotten all the way out there in the valley, Carmel is bustling with tourists and well-to-do townsfolk—there’s no danger of this beloved mission falling into disrepair.

In fact, the buildings are in fine fettle. This is one of the missions I’ve visited before, and when I was here two years ago, the façade was covered in scaffolding and tarps. So while the weather was brighter that first day, I’m glad I got to see it again without any distracting construction equipment around.

Carmel Mission has an interesting history, and a special place among its 20 siblings. It was the favorite of Blessed Junípero Serra, the priest who founded the first nine of the Alta California missions. He made Carmel the headquarters and seat of power of the entire chain, and directed operations for all the missions from this site until his death in 1784 (he’s even buried beneath the chapel floor). And in recent years Carmel has been made a basilica, giving it special status (and therefore protection) among the Catholic Church’s properties.

Like most of the missions, Carmel has seen many modifications over the years, and spent time in serious disrepair—but great pains have been taken to restore it to its original glory. As a result, it’s considered the most architecturally authentic of the missions. Later additions like steep rooflines and Victorian details have been removed, so what you see now is as close to the original as possible.

I love how Carmel perfectly marries different architectural styles into one lovely whole. There are the more “traditional” mission elements like tile rooftops and adobe colonnades—

—and then there’s the stone cathedral, with the more unusual Moorish influence (like that of Mission San Gabriel) of its ovoid dome and that spectacular star window.

But what I love best is the interior. The ceiling of the nave is arched, but not in the way a Gothic (pointed arch) or Romanesque (semicircular arch) nave would be. The shape here is a specific type called a catenary—the precise curve formed by a chain held with both ends up and its length hanging between them. Catenary arches aren’t found as commonly as other types (though since they perfectly balance the opposing forces of tension and compression, maybe they should be), but if you’ve ever seen the Gateway Arch in St. Louis, you’ve seen a catenary before.

(If you haven’t guessed, I’m a sucker for simple, mathematical perfection found in very old and unlikely places.)

The rest of the interior is a rabbit warren of brightly painted side chapels, living quarters and historical dioramas (warning: if dolls creep you out, you might want to skip this bit).

And when you wander back outside, you can breathe in the sea air and the fragrance of citrus and bougainvillea.