I was really hoping I might have had a sketch of a neon leaping frog (or something similar) for today’s post, but no such luck. Still, a leaping trout ain’t too shabby.

Hope your extra day shines like a neon beacon…happy leap year!

I was really hoping I might have had a sketch of a neon leaping frog (or something similar) for today’s post, but no such luck. Still, a leaping trout ain’t too shabby.

Hope your extra day shines like a neon beacon…happy leap year!

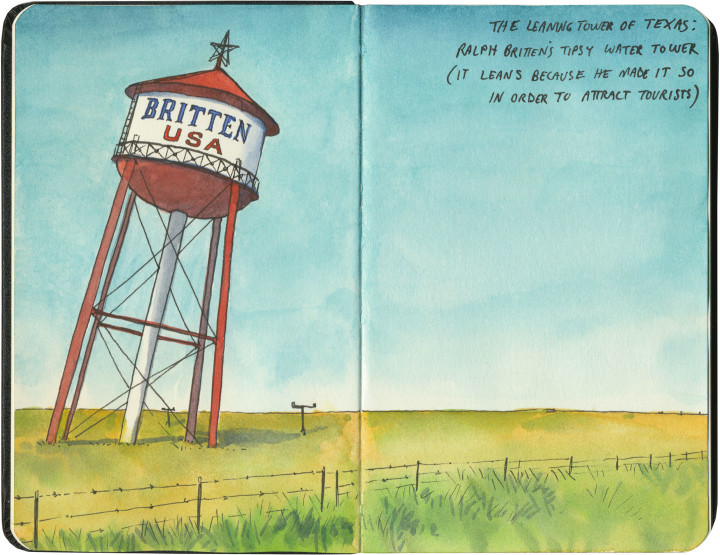

This post is part of an ongoing series called 66 Fridays, which explores the wonders of old Route 66. Click on the preceding “66 Fridays” link to view all posts in the series, or visit the initial overview post here.

I crossed Texas twice last year: once at its widest point (where we logged over 900 Texas miles), and once across the Panhandle, which is where Route 66 cuts a literal straight and narrow path. One of the main Mother Road attractions to visit there is the “Leaning Tower of Texas,” a ho-made gravitational wonder in the middle of the neverending plain.

At least, it used to be in the middle of nowhere. Now it’s surrounded on three sides by other nearby giants: a bunch of those enormous modern windmills, and an awful 19-story cross that isn’t so much delightfully hokey as disgustingly hideous.

So I flashed my laminated Artistic License, faced east as to miss most of the horizon clutter, and edited out the rest. I regret nothing.

After all, I was trying to capture the feeling of what it’s like to cross the Llano Estacado. Even today, when travelers have better navigational aids than makeshift stakes, it’s not hard to imagine how those first visitors must have felt.

Or maybe modern technology has a different meaning here. Maybe the fenceposts and telephone poles and windmills that dot the landscape now are this era’s stakes, marching in steady progress across an otherwise unknowable vastness.

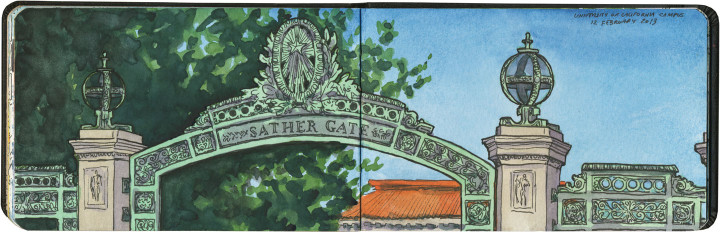

I didn’t have a ton of time this day, as I was actually playing hooky on a lecture to do this sketch. So I didn’t have time to explore much of the Cal campus, but at least I stole a few moments to stand on the threshold and get something down on paper.

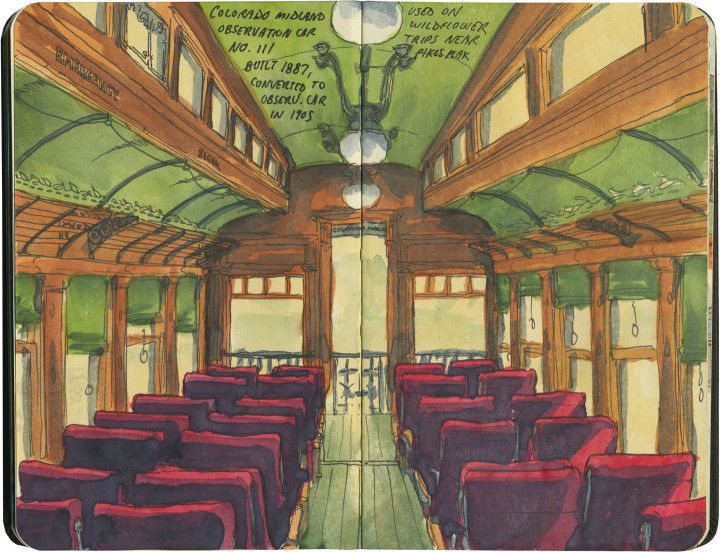

I love traveling by rail, though these days I don’t often get the chance to do it. So the next best thing is hanging out with historic trains—and sketching them, of course.

Besides, you know I’m a sucker for vintage lettering and logos—and a logo hound at a train museum is like a kid in a candy store.

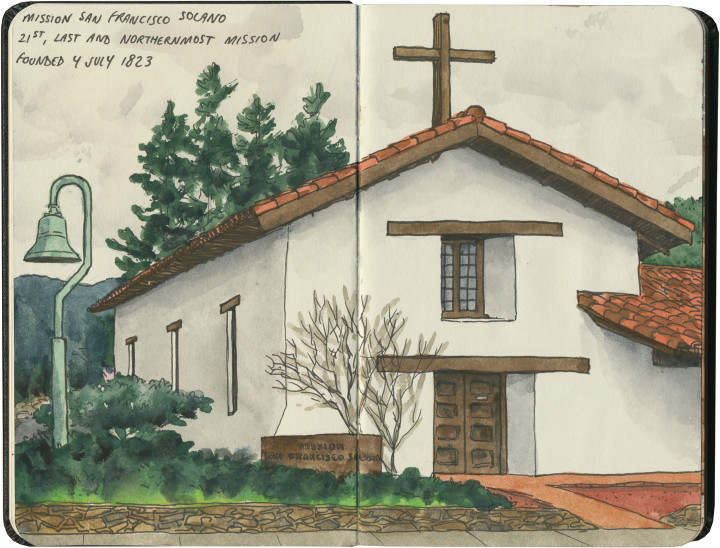

This is the twenty-first and final installment of my Mission Mondays series, exploring all 21 Spanish Missions along the California coast. You can read more about this series, and see a sketch map of all the missions, at this post.

Here we are, at long last! The very last California mission, in all its (understated) glory.

The northernmost mission in the Alta California system was also the very last one founded—fitting, since the while the missions in the middle are a jumble of out-of-sequence dates, the southernmost was also the first.

Mission San Francisco Solano is located at the center of the town of Sonoma, California’s famous wine-country gem. In fact, the first vineyard in Sonoma Valley was planted by the mission priests, for producing their own sacramental wine. And every October there is still a “blessing of the grapes” ceremony on site.

In 1835 the mission was deconsecrated, and Commander Mariano Vallejo turned much of the site into a military garrison to defend the interests of the newly-independent country of Mexico (Alta California was part of the Viceroyalty of New Spain until 1821, and wasn’t ceded to the U.S. until the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo). In the intervening years, the property was abandoned, fell into serious disrepair, and over time was gradually restored.

Today the mission is just one historic property among many in Sonoma, kitty-corner to the town plaza and surrounded by tidy streets and upscale shops. It’s hard to imagine what it must have been like before the valley was populated with modern residents and tourists—but it’s not hard to find the spirit of the place, and fall into a contemplative silence.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

That’s it! I hope you’ve enjoyed this virtual road trip with me. Now that we’ve visited all 21 missions, maybe it’s worth looking back at how far we’ve come. Here’s that map again:

And a list of all the posts for each site:

MIssion San Diego de Alcalá

Mission San Luis Rey de Francia

Mission San Juan Capistrano

Mission San Gabriel Arcángel

Mission San Fernando Rey de España

Mission San Buenaventura

Mission Santa Barbara

Mission Santa Inés

Mission La Purísima Concepción

Mission San Luis Obispo de Tolosa

Mission San Miguel Arcángel

Mission San Antonio de Padua

Mission Nuestra Señora de la Soledad

Mission San Carlos Borroméo del Río Carmelo

Mission San Juan Bautista

Mission de la Exaltación de la Santa Cruz

Mission Santa Clara de Asís

Mission San José

Mission San Francisco de Asís

Mission San Rafael Arcángel

Mission San Francisco Solano

Because I love travel stats, here are a few:

Miles traveled: Well, not counting the 1200 miles between San Diego and my house, nor any of the non-mission-related side trips I took along the way, I drove approximately 925 miles just between the 21 missions (I know my map says 600 miles, but modern highway routes and some required back-and-forth affected the actual driving distance).

Time period in which missions were founded: Between 1769 (San Diego) and 1823 (San Francisco Solano).

Number of missions where all or most of the structure is a 20th-century replica: 7 (All but one of those are in the northern half of the chain.)

Number of missions that still have consecrated churches or chapels on site: 18 (La Purísima, Santa Cruz and San Francisco Solano do not.)

Number of times I didn’t see a mission from the inside: 5 (Two were closed when I got there, one was in the middle of mass, one had a wedding going on, and another was hosting a quinceañera.)

Most touristy: San Juan Capistrano had the gift shop and theme-town thing down, but I saw the greatest number of actual tourists at Santa Barbara. There were gobs and gobs of them.

Least touristy: San Antonio de Padua, where I was the only one there—though La Soledad was a close second, most likely because it’s literally in a farm field and nearly unmarked.

Most underrated: This one’s hard, because almost all of them are underrated in some way. But I’m going to go with San Miguel, because it’s such a stunning place, and the adjacent freeway just sends people flying right on by.

Best architecture: Tie between San Juan Capistrano and Mission Carmel, but with a special shout-out to the Moorish design of San Gabriel—and to the folks at Mission San Jose for being sticklers in choosing a period-authentic replica over a glitzy showpiece.

Overall favorite mission: La Purísima. Hands down. But the runner-up remains San Juan Bautista, which was my first love.

Final thoughts:

The thing that most struck me is the contrast between the missions—not only the various architectural styles, but the varying states of repair and disrepair. I would love to see an integrated system like the National Parks System has, encouraging tourists to visit all 21 missions and share a common pool of resources, staff and funding for upkeep and repairs.

Whatever system there may or may not be in future, it doesn’t change the fact that all of the missions are worth visiting and preserving. I’d do the whole trip again in a heartbeat—and I hope I get the chance to do just that, someday.

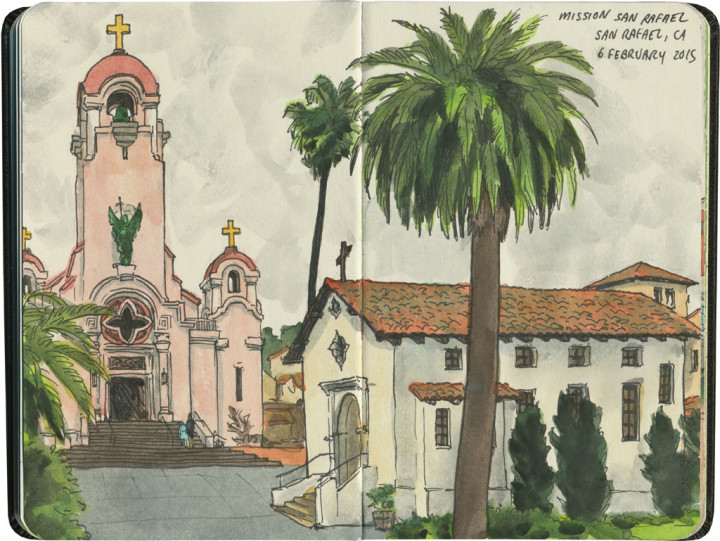

This is the twentieth installment of my Mission Mondays series, exploring all 21 Spanish Missions along the California coast. You can read more about this series, and see a sketch map of all the missions, at this post.

This is yet another replica mission—making it compare less favorably to places like San Francisco or San Juan Capistrano, and one of the least visited in the chain. In fact, when I later had dinner with a local and told him what I’d done that day, he said, “Yeah, but it’s been totally rebuilt, so it hardly counts.” Well, fair enough. Still, I’m a completist, so here we are.

Mission San Rafael Arcángel completes the trio of missions named for the three arcangels (Gabriel, Michael and Raphael). Originally it was built as an asistencia or sub-mission (there are still several sub-missions still standing, but I didn’t visit any of them—it was hard enough to get to the 21 main missions!), but it was “upgraded” to full mission status in 1822.

The pink tower of St. Raphael’s Church is the most eye-catching feature of the complex, but what’s more interesting to me is that the mission served as (what would become) Marin County’s first hospital. Taking advantage of the superior air quality to that of San Francisco, San Rafael was organized as a sanitarium for the local Indigenous tribes.

Sadly, there’s really no trace of the original mission left today—which makes the old wall at Santa Cruz seem like precious treasure. The current buildings are twentieth-century replicas, and not even the layout of the original complex has been preserved. So I can see where my local acquaintance was coming from, I guess. Still, I can’t write the place off entirely—whatever form it takes, it’s a link to California’s past.

As far as I’m concerned, it still counts.

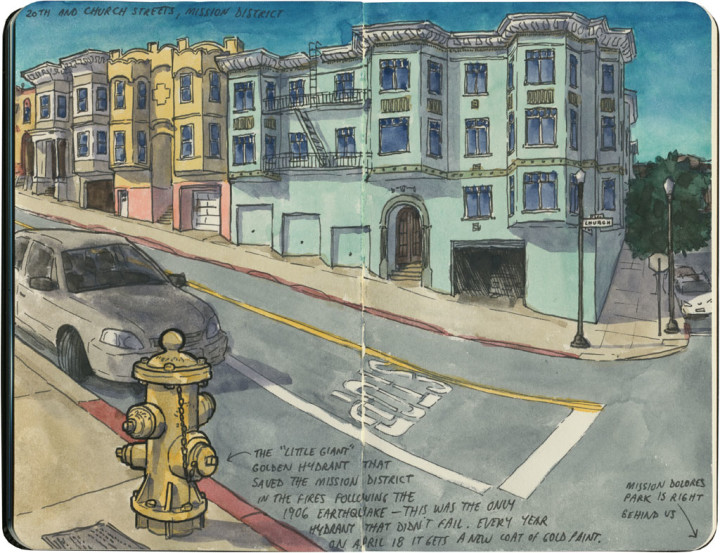

Just a couple of blocks from Mission Dolores is a tiny, inanimate hero—one that saved the Mission District from ruin over a century ago. The story of San Francisco’s 1906 earthquake is a famous one, but not everyone knows that it’s actually the fire which immediately followed that did most of the damage. With the water mains broken by the quake, most of the city’s hydrants ran dry, allowing the fire to take out whole neighborhoods. In the end 80 percent of the city was destroyed.

In the Mission District, just one hydrant was miraculously still working: the one at 20th and Church Streets. The problem was that the hydrant was perched near the top of the hill, high above the horse-drawn fire wagons stationed along Market Street. The exhausted horses couldn’t pull the wagons up to the hydrant—so the hundreds of refugees gathered across the street in Dolores Park pitched in to help, pulling and pushing the wagons uphill by hand. The entire neighborhood fought the flames when they reached 20th Street, and after a seven hour battle, the Mission District declared victory. And to this day, every April 18 at 5:12 am (the date and time of the 1906 quake), the descendants of those who were there meet to give the “Little Giant” a fresh coat of gold paint.

It’s a great story, full of swashbuckling detail—much of which I’ve had to leave out for the sake of brevity. So I’ll just leave you with my favorite part of the tale: with the water mains and every neighboring hydrant broken, nobody could ever explain where the water came from that kept the Little Giant up and running.

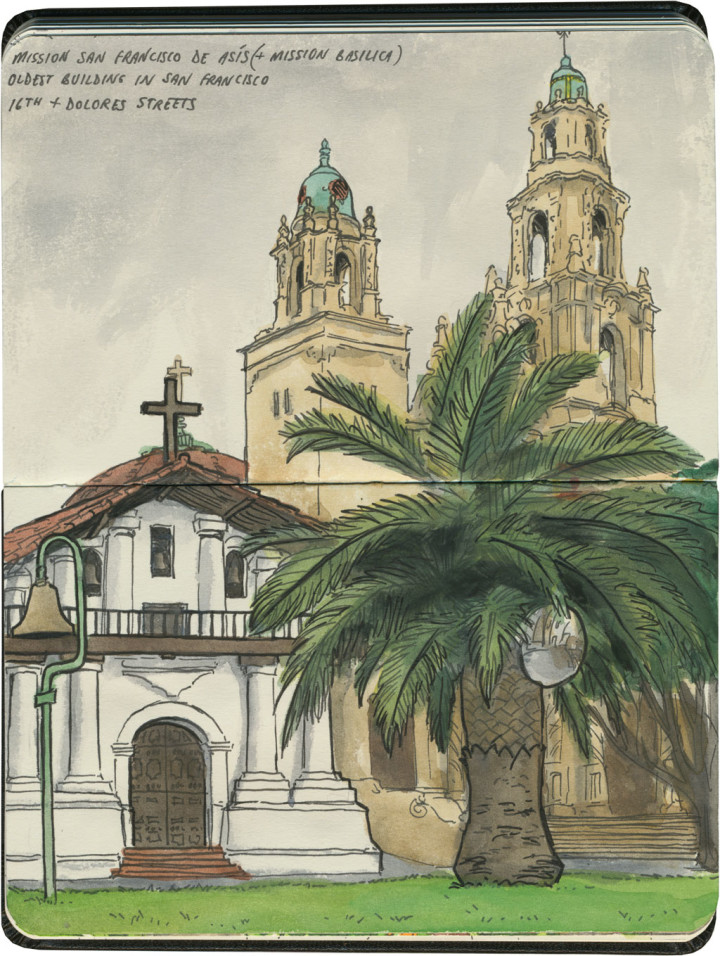

This is the nineteenth installment of my Mission Mondays series, exploring all 21 Spanish Missions along the California coast. You can read more about this series, and see a sketch map of all the missions, at this post.

Mission San Francisco de Asís (or Mission Dolores, if you prefer the nickname) is the centerpiece and namesake of San Francisco’s Mission neighborhood. Yet the mission itself, tucked away on a residential block, behind towering palms and ficus trees, seems to get lost amid all the trendy restaurants and busy hipsters flooding the rest of the neighborhood. It’s even overshadowed by the tall spires of the basilica next door—many people don’t even know that the squat adobe building is the actual mission, not the towering cathedral.

As an aside, I did this one out of order… as I happened to be in the Bay Area at the beginning of my trip, rather than the end, I did the last three missions first, in reverse order.

This is one mission I knew well—at least from the outside. Every time I’m in San Francisco, I end up with errands to run, or people to see, or at least a route that takes me through this neighborhood. So Mission Dolores has gone from familiar landmark to old friend. The interior was a mystery to me, though, and it took all of three seconds to know I’d found a hidden gem. I stepped one foot inside—

—and that ceiling just took my breath away.

The mission chapel is no longer a consecrated church, but it still deserves plenty of reverence. After all, Mission Dolores is the oldest intact building in San Francisco—which, considering the devastation of the 1906 earthquake (not to mention all those other destroyed missions), is really saying something.

So if you find yourself in San Francisco, on your way to Tartine (come on, I know I’m not the only one), stop here first. I promise it’ll be worth the detour—and I can’t think of a better place to pay homage to the City by the Bay.

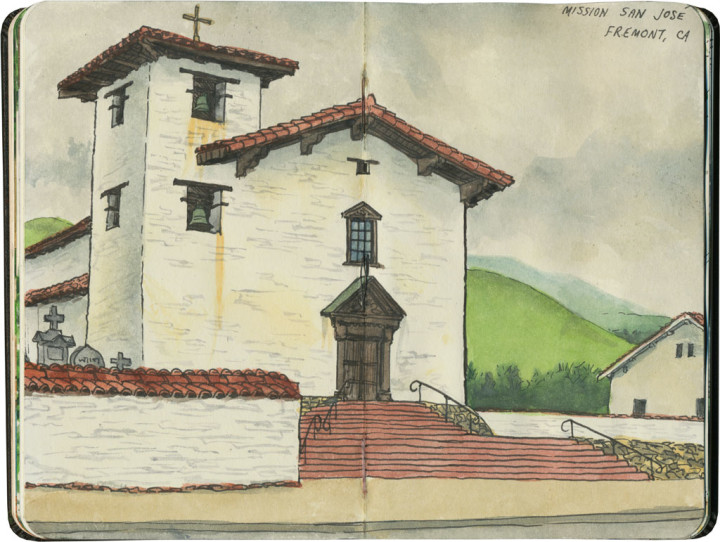

This is the eighteenth installment of my Mission Mondays series, exploring all 21 Spanish Missions along the California coast. You can read more about this series, and see a sketch map of all the missions, at this post.

This place might be a little confusing if you let yourself get tripped up by the name. Mission San José is not actually in San Jose—Santa Clara is the mission upon which the city of San Jose is founded. Mission San José is further north, on the east side of the Bay and in the modern-day suburb of Fremont. It’s perched on the edge of the Contra Costa hills, surrounded by a Gold Rush-era enclave that’s itself surrounded by contemporary ‘burbs. Clear as mud, right?

Mission San Jose isn’t the northernmost in the chain, but because of its location on the east side of the Bay, it was actually the very last one I visited. In fact, its location rather defies the “rule” of placing the missions a day’s horseback ride apart from one another—unless you put your horse on a boat to cross the bay to San Francisco, I suppose.

Once again, what’s there now is a totally a rebuilt mission—but the place is a pleasant surprise. Of all the replicas, this one is possibly the most faithful to the original style of architecture.

Even the interior of the church is authentic in every detail. I loved the wooden, unadorned ceiling.

They even managed to preserve some old wall remnants and original foundations, creating a nice mix of old and new. The overall result has some of the character of a place like San Juan Capistrano, and the tidiness of the restored missions like San Luis Obispo.

So while the northern missions might not all have the style and substance of the ones in the south, there’s still plenty that’s worth discovering. And this one, in particular, is well worth making a pilgimage to the ‘burbs.

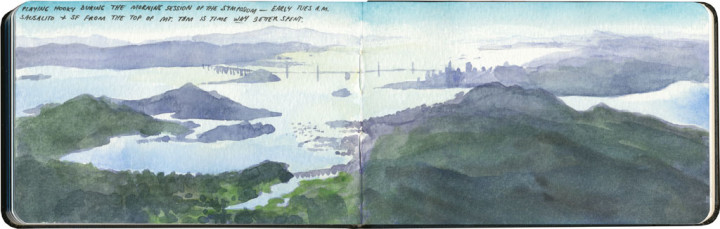

On the morning I did this sketch, I was supposed to be sitting in a darkened lecture hall, listening to a bunch of scholars talk about art. But I just couldn’t do it. On a day like that, it seemed criminal to pass up such a beautiful place. So I jumped in the car and drove in the opposite direction—in the same time it would have taken me to get to the auditorium, I had reached the top of the world.

Posting this sketch has me remembering that I do this a lot. I have a long history of throwing the itinerary out the window and going off on my own to explore instead. And I gotta say: every single time, without fail, it’s been precisely the right choice to make.