This post is part of an ongoing series called 66 Fridays, which explores the wonders of old Route 66. Click on the preceding “66 Fridays” link to view all posts in the series, or visit the initial overview post here.

One of the most well-known—and most-hyped—tourist traps along Route 66 are the Meramec Caverns. Whether or not the caves actually live up to the hype is not something I can weigh in on, I’m afraid: by the time we got there, they’d closed for the evening. But that’s okay—while I’m always up for a good tourist trap (neon signs inside the caves!), and I’d love to see the place that was allegedly the hideout of Jesse James, what really interests me most is the hype itself. And on our trip I didn’t have to worry about missing out on that.

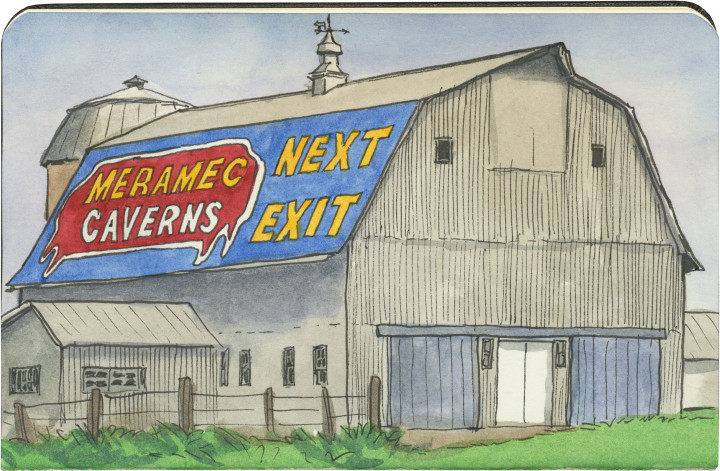

When it comes to advertising, Meramec Caverns seems to have taken a leaf from the playbook of Wall Drug, which opened just two years before the Caverns transitioned from local curiosity to tourist entertainment complex. Wall Drug had enormous success with advertising to travelers by way of hundreds of inexpensive, hand-painted wooden billboards placed in farm fields all over the northern Plains. Les Dill, the owner of the Caverns, offered farmers in 14 states a free paint job on their barns—as long as they were willing for the design to include a giant Meramec Caverns ad on whatever wall or roof panel faced the road. By the 1960s there were hundreds of Meramec barns in 40 different states, all beckoning travelers to the Ozarks.

Oh, and you might also be interested to know that Dill was also one of the earliest adopters of the humble bumper sticker, cottoning onto the idea of cars as mobile billboards. Now, I still don’t think there’s a more elegant bumper sticker than “Where the heck is Wall Drug?” but Meramec Caverns had the idea first.

There are still a handful of Meramec barns around today, and some of the best (and most lovingly maintained) are along the Mother Road. They vary in design, and some—like the one above—look a bit like some sort of cryptic code for those in the know.

Well, thanks to Dill’s ingenious marketing strategy, I am in the know now—and you can bet I’ll return one day, following the signs back to the Caverns, barn by barn.