This post is part of an ongoing series called 66 Fridays, which explores the wonders of old Route 66. Click on the preceding “66 Fridays” link to view all posts in the series, or visit the initial overview post here.

It’s easy to take for granted the fact that the American West is crisscrossed with highways nowadays, but those highways didn’t get there by chance. If you look closely at the routes those highways take, you can give yourself an excellent crash course in history, both human and natural. Overland exploration, trade routes, desert basins, animal migration, continental drift…all these things and more are hinted at by the map sketched out by the U.S. highway system.

Let me explain what I mean. If you happened to grow up in the Midwest, chances are your mental map would be dictated by a grid that follows the cardinal directions. In the Great Plains, particularly, where the landscape is mostly flat, dividing property lines and town borders into a standard grid makes the most sense. Much of the United States west of the Appalachians is arranged this way, in fact, in a basic grid called the Range and Township system. The system overlays a simple framework of one-square-mile sections over the entire western two-thirds of the country, dividing the landscape into rangeland for farming and six-mile by six-mile townships. Interestingly enough, we have Thomas Jefferson to thank for this system, which he devised in 1785 as a way to manage the vast swaths of land that, after the Revolution (and some years later the Louisiana Purchase), now belonged to the U.S. His reasoning, I think, was both practical and lofty: as a farmer himself, he was looking for a workable alternative to the inherited system of Metes and Bounds, England’s age-old framework for managing farmland and water access. While that system worked for the colonies, each roughly comparable in size and topography to what they knew in the Old World, the old framework wasn’t scalable to the size of the new West—particularly when tracts of land were being sold off sight-unseen to settlers and prospectors. But beyond the practical logic, I think Jefferson had more philosophical motives behind his plan. This is the guy who designed Monticello, after all, a monument to neoclassical thinking and an homage to ancient Greece and Rome. The Range and Township system applied a sense of order—however illusory—to the uncharted wilds of the West. It brought rational thought and a sense of opportunity to an area associated with chaos and the fear of the unknown.

If you’ve ever visited the Great Plains, you can still see Thomas Jefferson’s plan in evidence, from the straight-as-an-arrow farm roads in rural areas, to the faithful system of thoroughfares in cities like Tulsa or Dallas, where the roads always travel from A to B in a straight line, with traffic lights appearing like clockwork at precise one-mile increments, and tenth-of-a-mile residential blocks in between.

But here’s the problem: Thomas Jefferson never laid eyes on the West he gridded out like a piece of paper. He never saw nature’s rebuttal to rationality in the Rockies or the Colorado Plateau. It’s all well and good to have a sensible grid in a flat place, without major physical features to interrupt the plan. But in many parts of the West, Jefferson’s tidy squares becomes utterly useless. You can’t easily farm a quadrangle of land that’s bisected by a canyon, and you can’t run a road up and over a mountain. Travel in a straight line is impossible in many, many places. As everyone from Chief Joseph to Lewis and Clark to highway engineers could tell you, there are some places in the West where only one route overland is possible—or none at all.

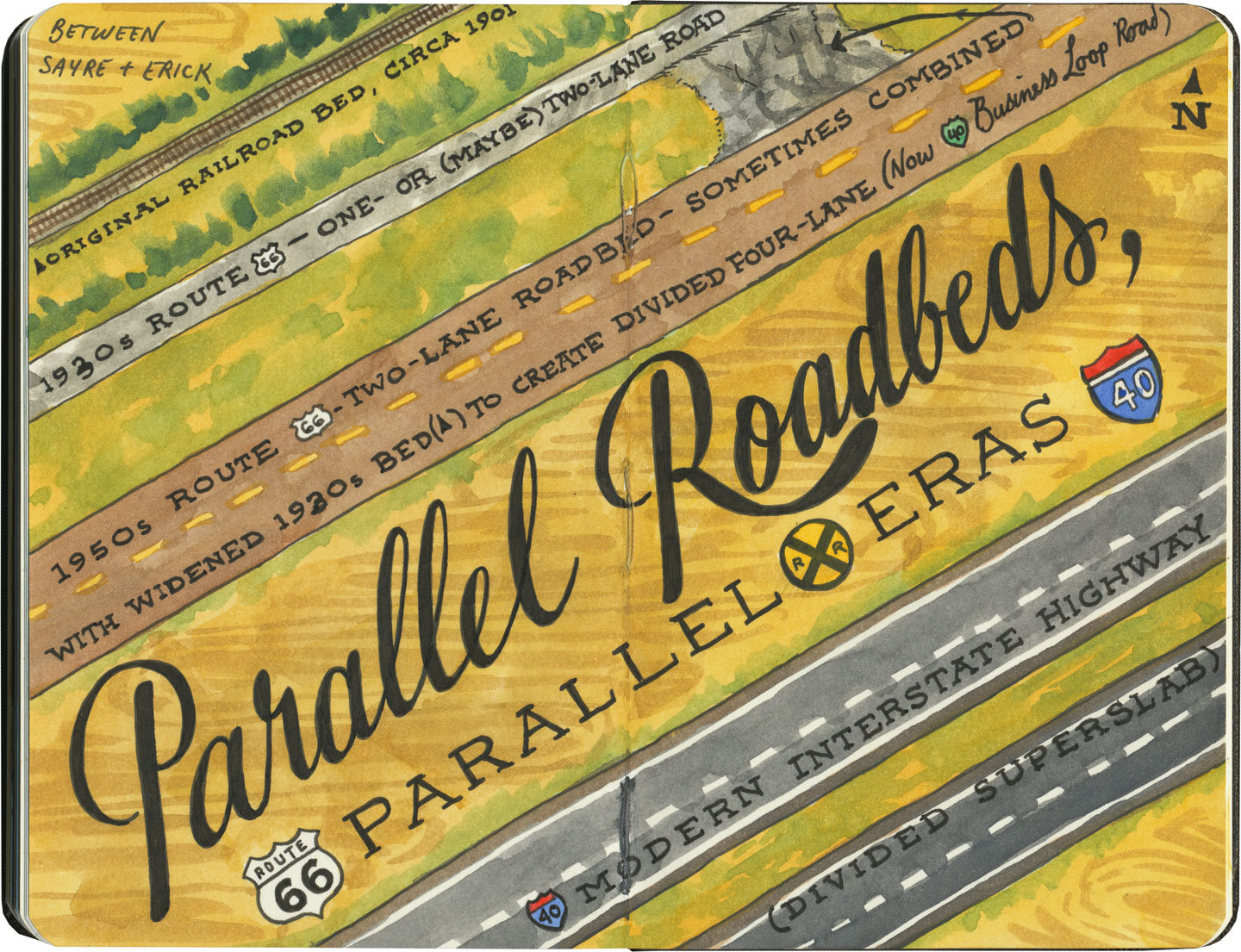

So if you look at a modern highway map of the western half of the United States, the limitations geography places on rationality are obvious. You can see precisely where the Corps of Discovery found their way to the Pacific Northwest, or where the stagecoaches hauled goods to Santa Fe, or how the Mormon pioneers tumbled out of the mountains to the Great Salt Lake, or the supply route linking the California Missions to Mexico. It’s all there, because centuries later we’re still traveling the exact same routes that humans always have, dodging mountains and following water to whatever their destinations were. The Conestoga wagons followed the game trails and trade routes of the various Indigenous peoples. The railroad followed the pioneers’ wagon tracks. The first pavement slabs paralleled the railroad grade, and modern Interstate freeways zoom right over many of those original roadbeds and trailways. Even the technology of conveyance was based on the older methods of travel—just look at the wheel base on a modern car, whose width matches that of railroad cars, themselves directly descended from the lineage of horse-drawn wagon measurements.

As you can probably guess by my long-winded introduction here, this stuff ties square in with Route 66 and the path it cuts to the Pacific.

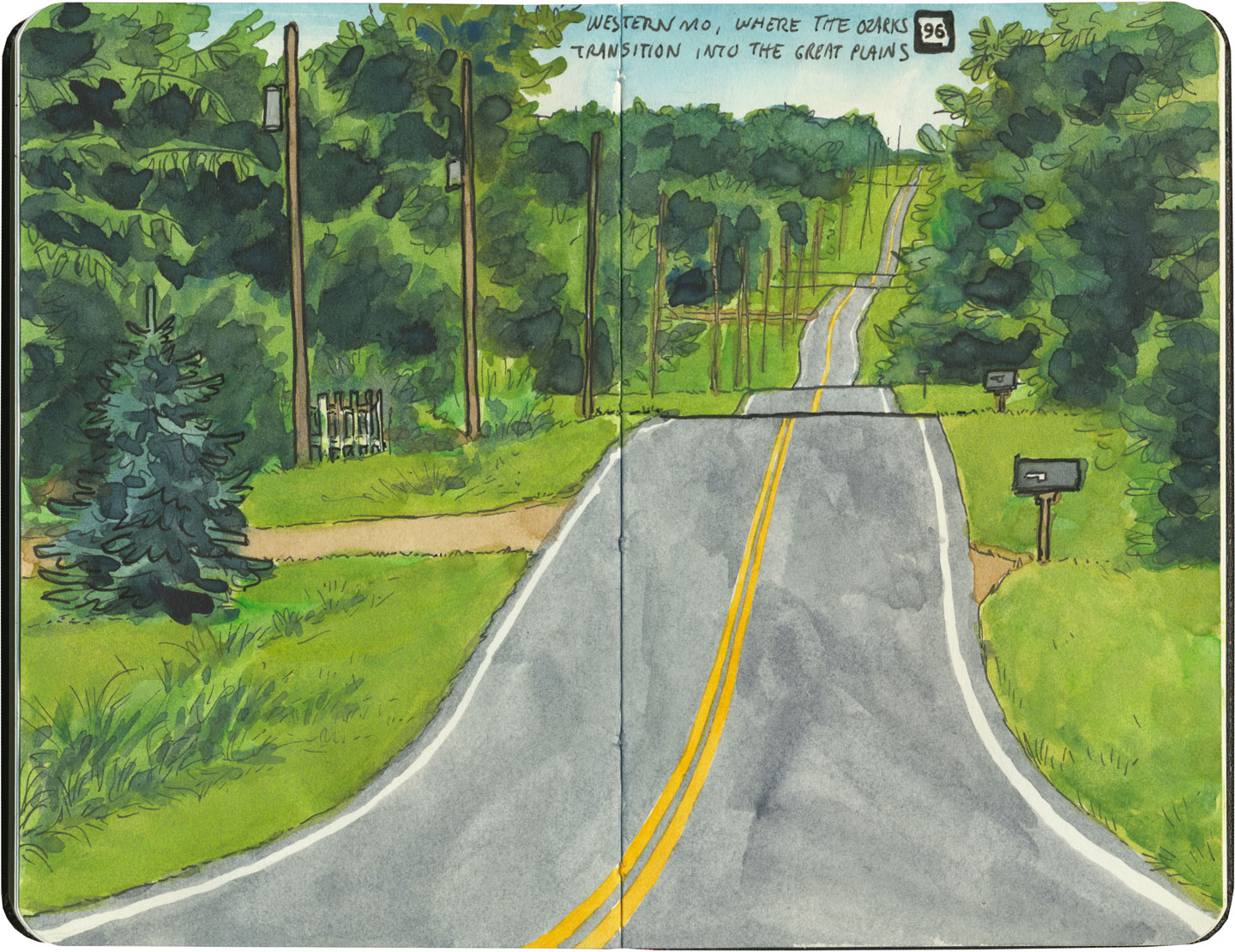

There are many places along Route 66 where you can see this progression of transportation history unfold before your very eyes. In flat places like central Illinois or eastern Oklahoma, there was no reason to reuse the same roadbed over and over again—they had all the land in the world at their disposal, and nothing to impede their path. So they simply built the new road alongside the old—over and over again.

The result is a network of parallel lines, each wider than the last, each laid down at a different point in recent history. In these places, the land acts like a palimpsest, marked over and over again with new traceries of roadbeds, while the old ones, though crumbling in disrepair, still remain visible.

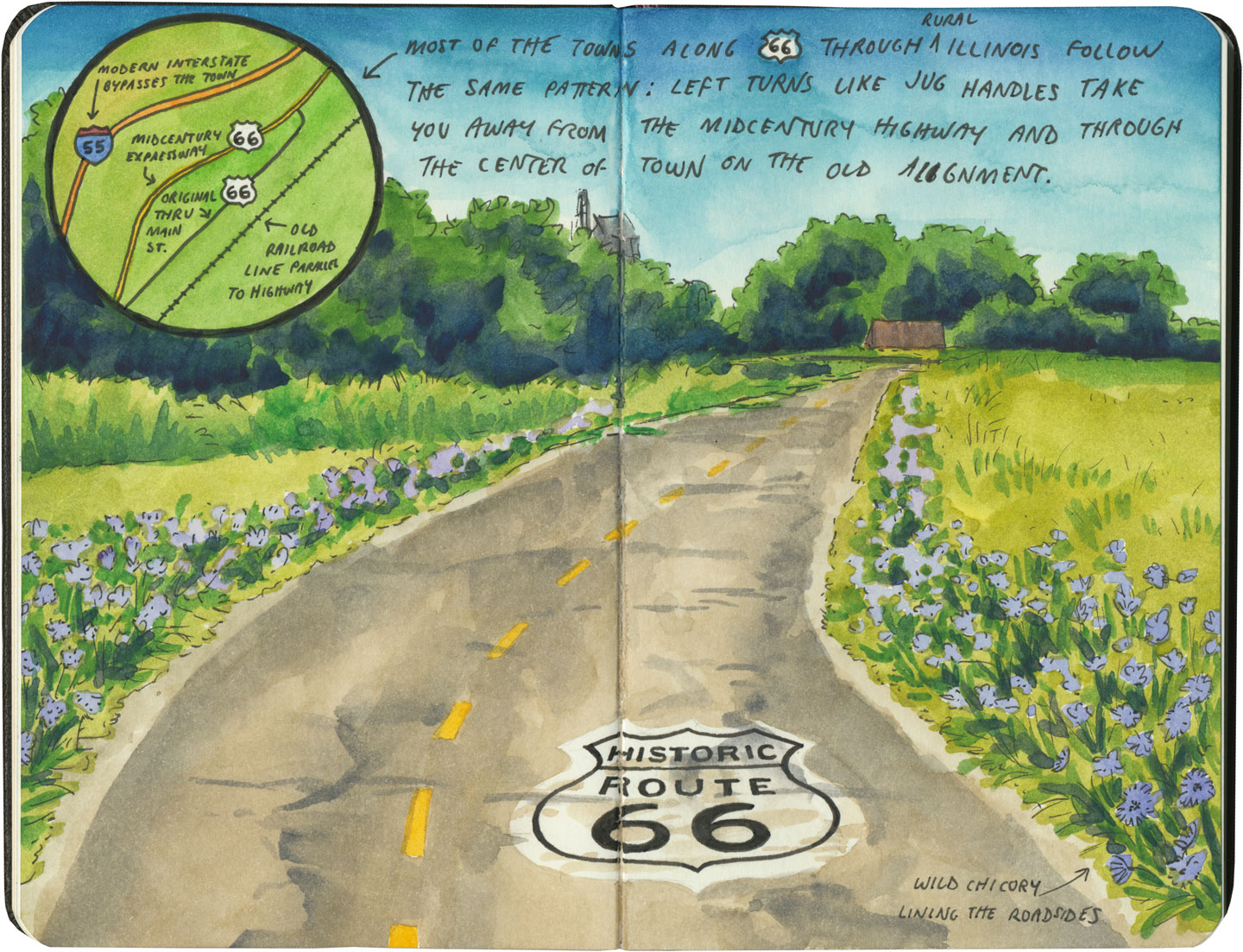

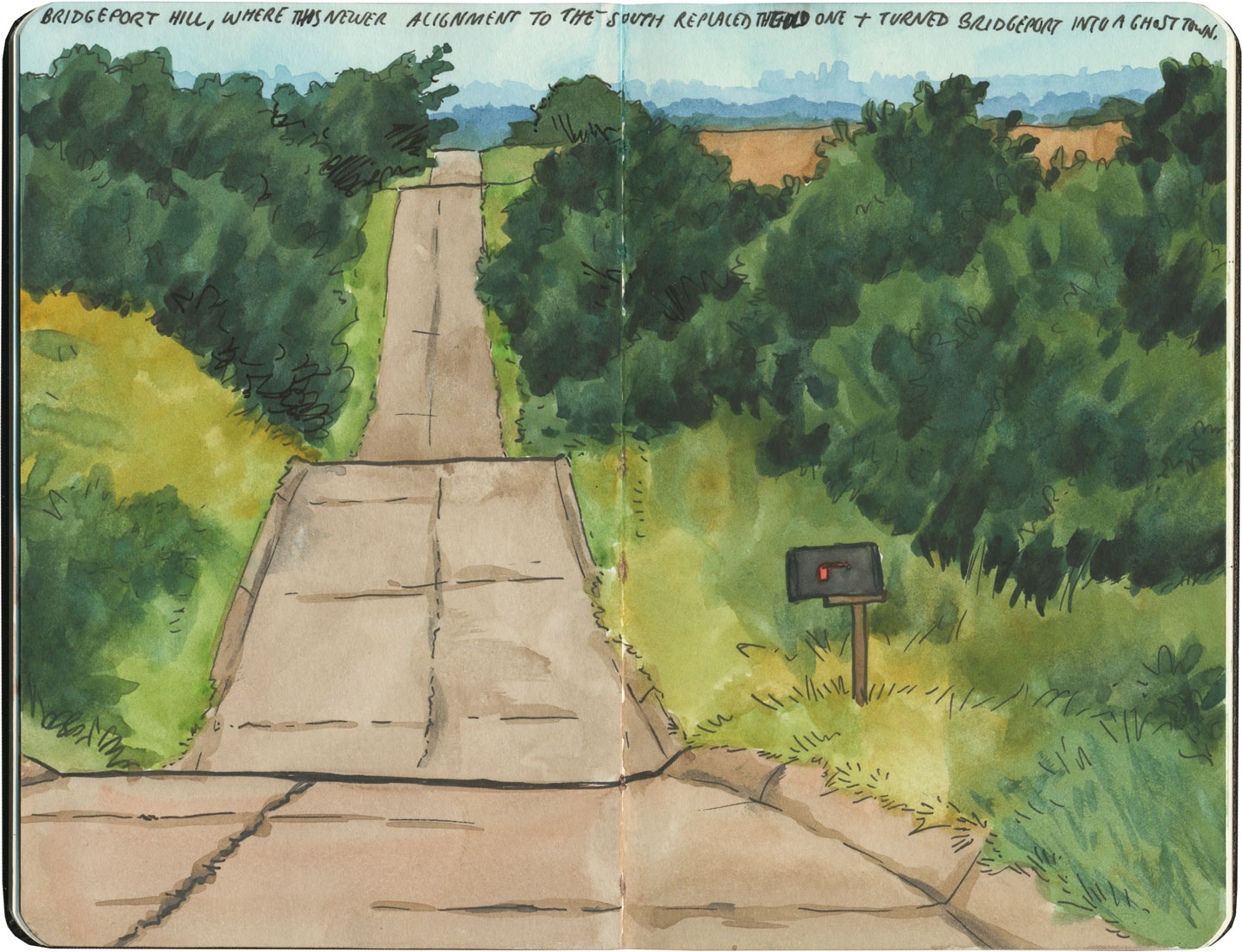

Since Route 66 was decommissioned as an official national highway, there are places where it’s difficult to discern the original route. The old roadbed might be there, but the Mother Road can get lost amid a modern tangle of frontage roads, diversions, and replaced pavement.

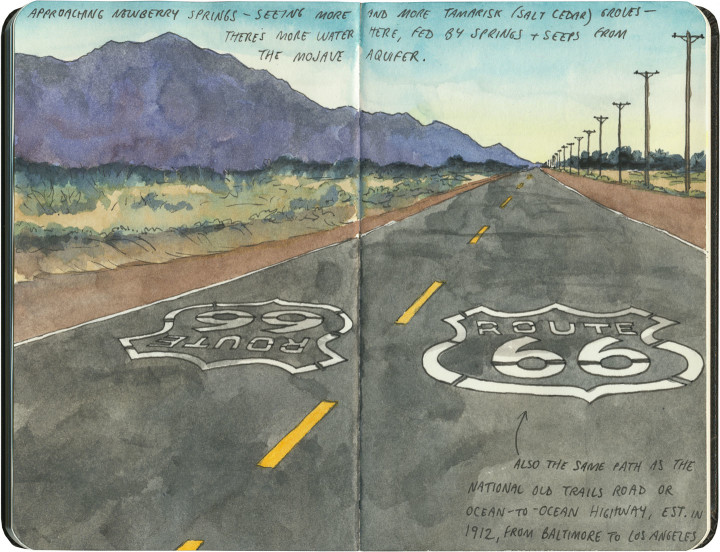

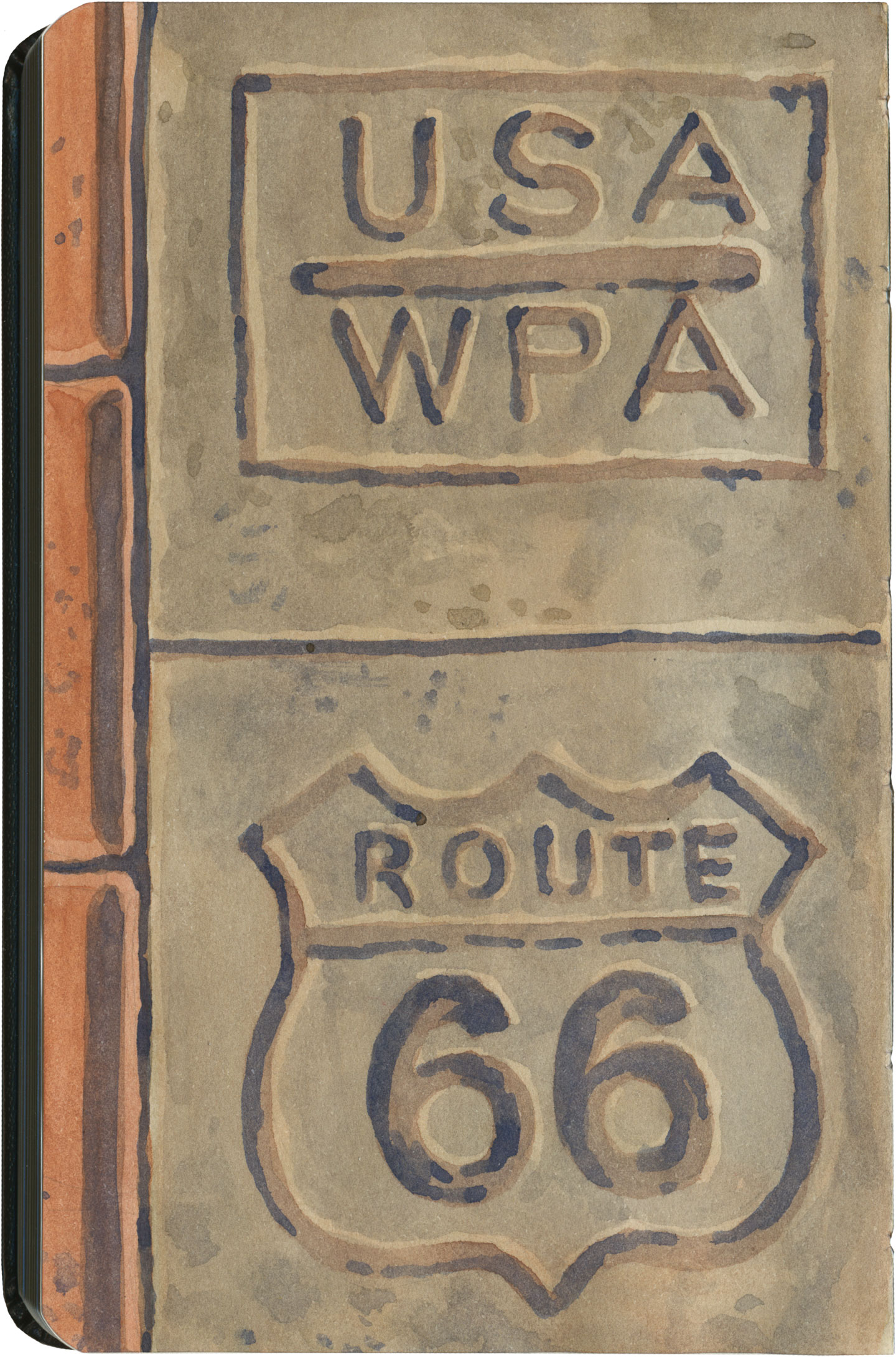

Part of the joy of traveling Route 66 is learning to recognize the old road. In some places, the path is lit up like a beacon with painted pavement and restored waymarking…

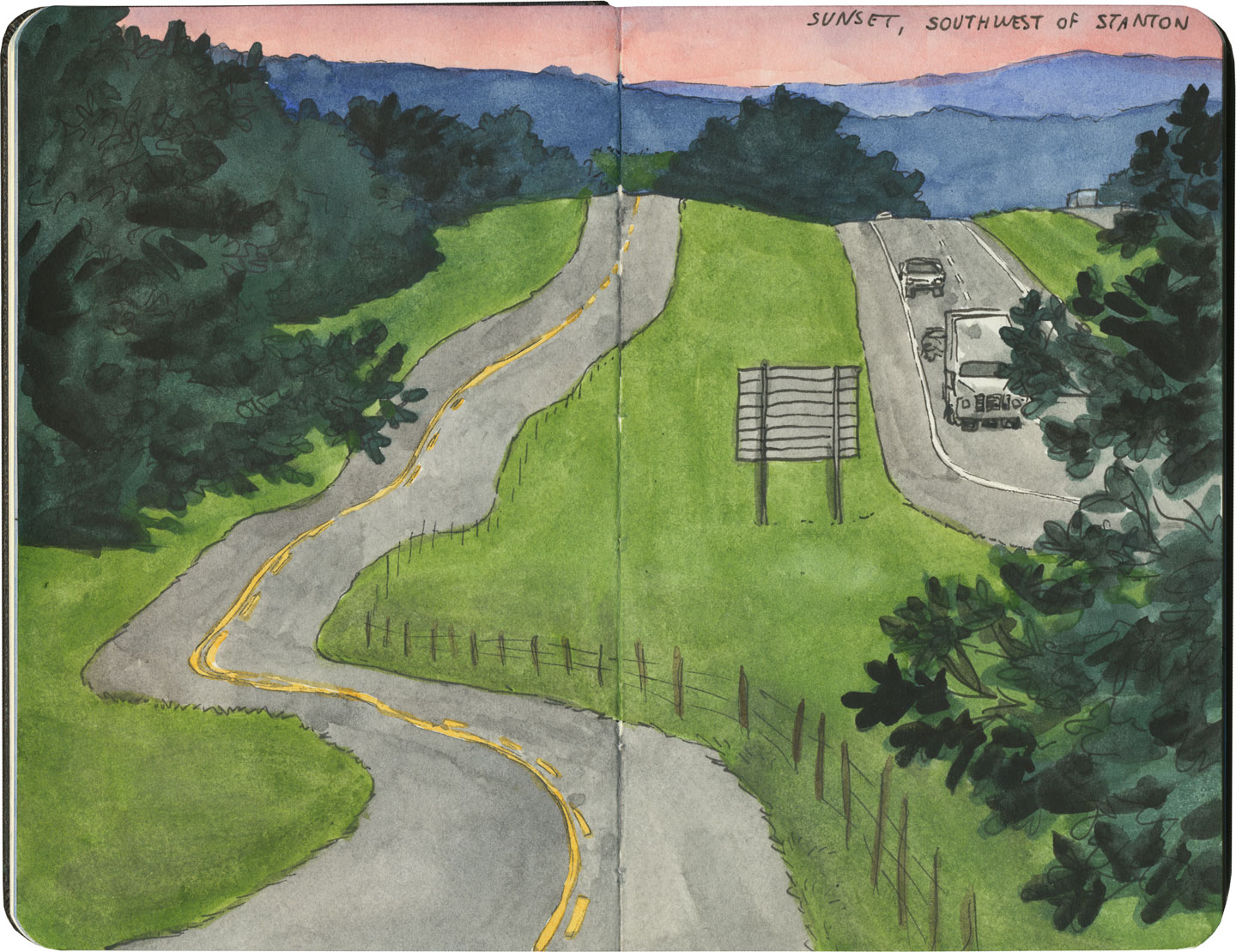

…in others, tracing the original marks on the palimpsest becomes something of a quest.

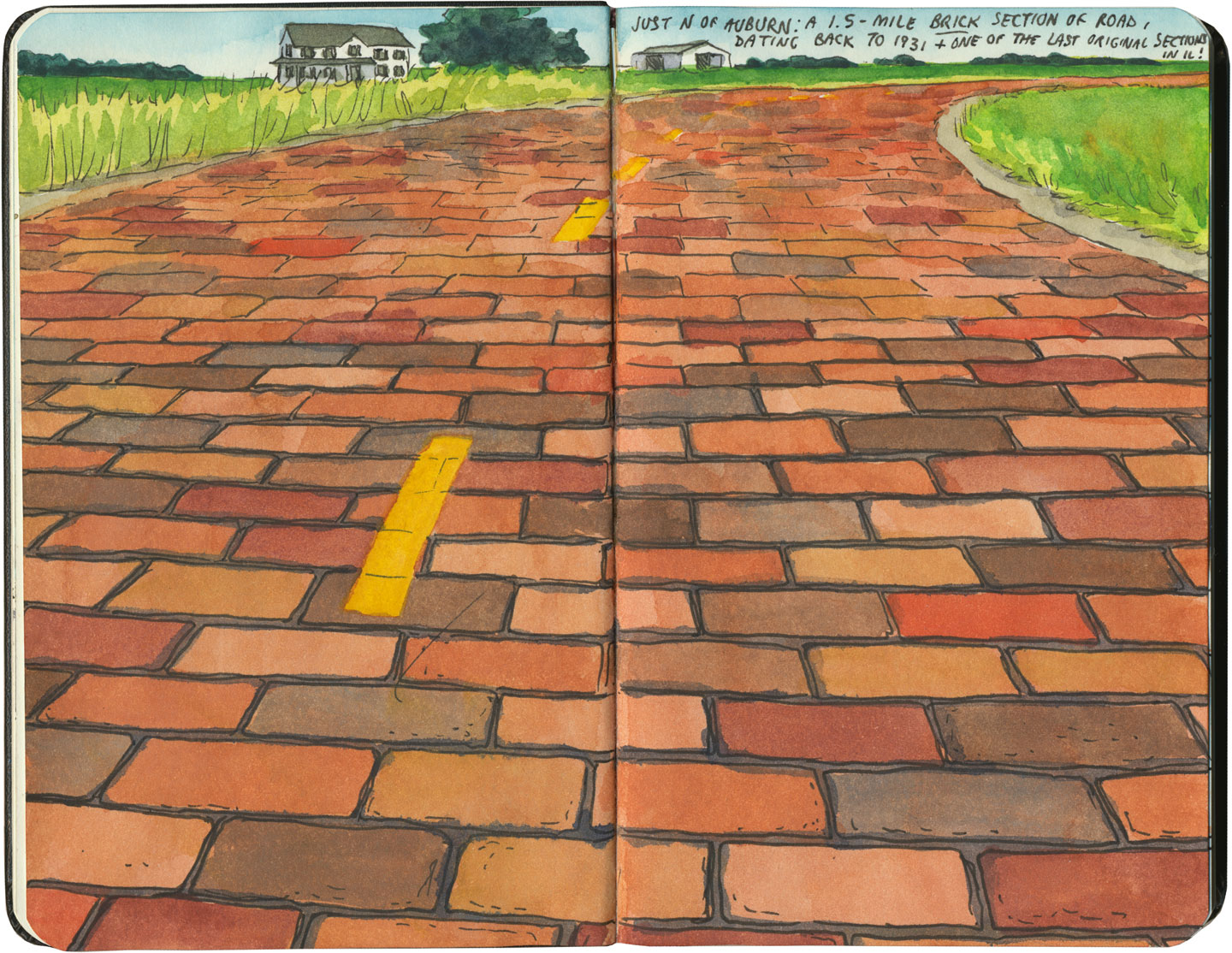

And then there are the places where the original pavement itself becomes the attraction along the way—like this gorgeous stretch of brick roadway in Illinois, paid for in the 1930s by a brick magnate and lovingly maintained as a curious relic of the past.

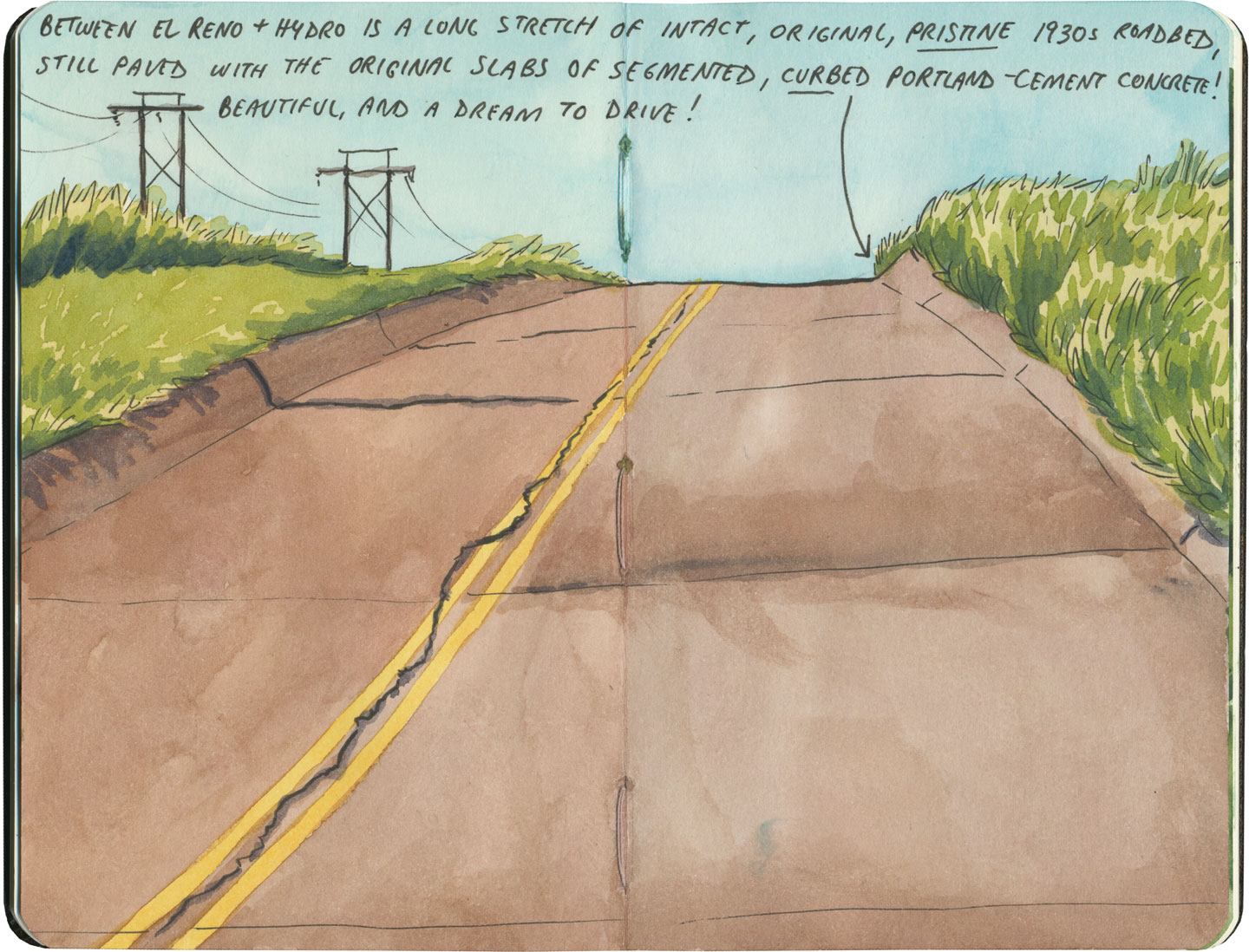

My favorite of all was the long section of 66 that traverses central Oklahoma: the combination of good craftsmanship and a remote locale has preserved the original roadbed impeccably. It sounds nerdy to say it out loud, but I dare any 66 enthusiast not to feel a thrill when seeing that curbed Portland cement.

By the end of our journey, we’d gotten really good at spotting the difference between old and new along the way. And whenever we lost the thread of the route (easily done, since there are so many alignments, many of which have been replaced or buried under modern roads), it became easier and easier to spot the hints that would lead us back to the Mother Road.

What led me to travel Route 66 was a love of history and Americana, and a desire to travel a well-worn and well-loved path. I had no idea that it would be so much more—and something much closer to the feeling of solving a mystery. Beyond the fun of diners and neon, there’s a richer, subtler 66 to be discovered, if you’re willing to look a little deeper. All the clues are there—some of them stamped right into the pavement underfoot.