I didn’t happen to be in St. Louis on the Fourth of July, but I might as well have been, judging by how the Old Courthouse was decked out inside. Wishing a safe and happy Independence Day to all my American readers!

I didn’t happen to be in St. Louis on the Fourth of July, but I might as well have been, judging by how the Old Courthouse was decked out inside. Wishing a safe and happy Independence Day to all my American readers!

This post is part of an ongoing series called 66 Fridays, which explores the wonders of old Route 66. Click on the preceding “66 Fridays” link to view all posts in the series, or visit the initial overview post here.

Route 66 has ruined souvenir shops for me forever. I mean, I thought I had high standards after growing up on Wall Drug, but the Mother Road is home to all manner of souvenir shops housed in buildings ranging from interesting to downright nuts. Whether you’re buying snow globes in a Tipi or braving wild burros to get to your t-shirts, you’ll never have to worry about trying to find a postcard in a big box store on this road.

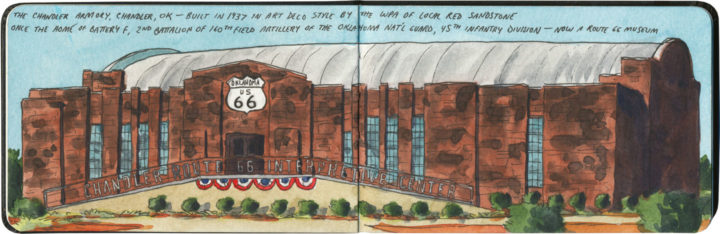

In keeping with tradition, Chandler, Oklahoma, sells its souvenirs in an honest-to-goodness fortress. Of course, the souvenirs weren’t what we came for—we came for the gorgeous Works Progress Administration (WPA) architecture and the top-notch museum and interpretive center inside. But you know, since we were already there and all, we figured it would just be wasteful not to stock up on shield-shaped fridge magnets and keychains at the same time…

This post is part of an ongoing series called 66 Fridays, which explores the wonders of old Route 66. Click on the preceding “66 Fridays” link to view all posts in the series, or visit the initial overview post here.

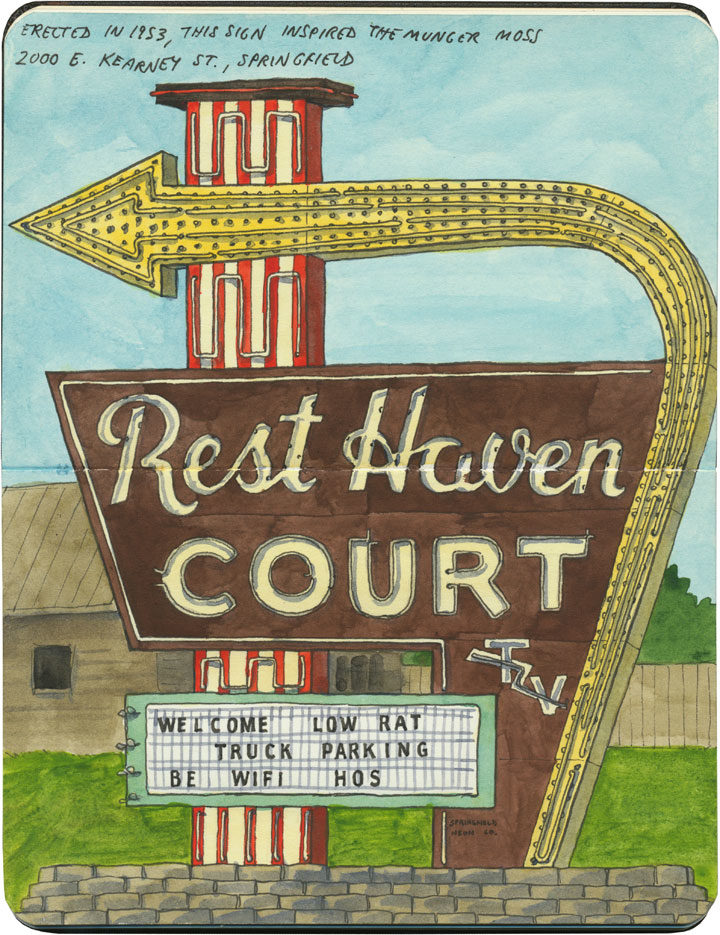

Compared to some of the other outrageous neon specimens along Route 66, this one seems downright pedestrian. Still, there’s a kind of midcentury perfection to this one, from the gorgeous script lettering to the jaunty lightning bolt through “TV.” And there’s something familiar about the shape of the sign, as well, as if one had seen it before…

Ah, right. One has. This brighter, showier version is just fifty miles away in Lebanon, MO—it was built (by the same neon company, no less) in tribute to the Rest Haven sign, which the owner of the Munger Moss had admired when it was erected just a year or so before, in 1953. And both signs are a clear homage to one of the most famous neon sign designs in America: the one known simply as the “Great Sign,” which began marking Holiday Inns around the U.S. in ’52.

I’m guessing there wasn’t a whole lot of respect for intellectual property among sign scribes of the time, because this sort of design pilfering was pretty common—but I find I just can’t get too riled up about this case. For one thing, that basic Great Sign look appeared in knock-offs all over the country—clearly people thought if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it. For another, I confess I felt a little thrill when I got to see that little TV lightning bolt again: it was like a moment of Deja Googie.

This post is part of an ongoing series called 66 Fridays, which explores the wonders of old Route 66. Click on the preceding “66 Fridays” link to view all posts in the series, or visit the initial overview post here.

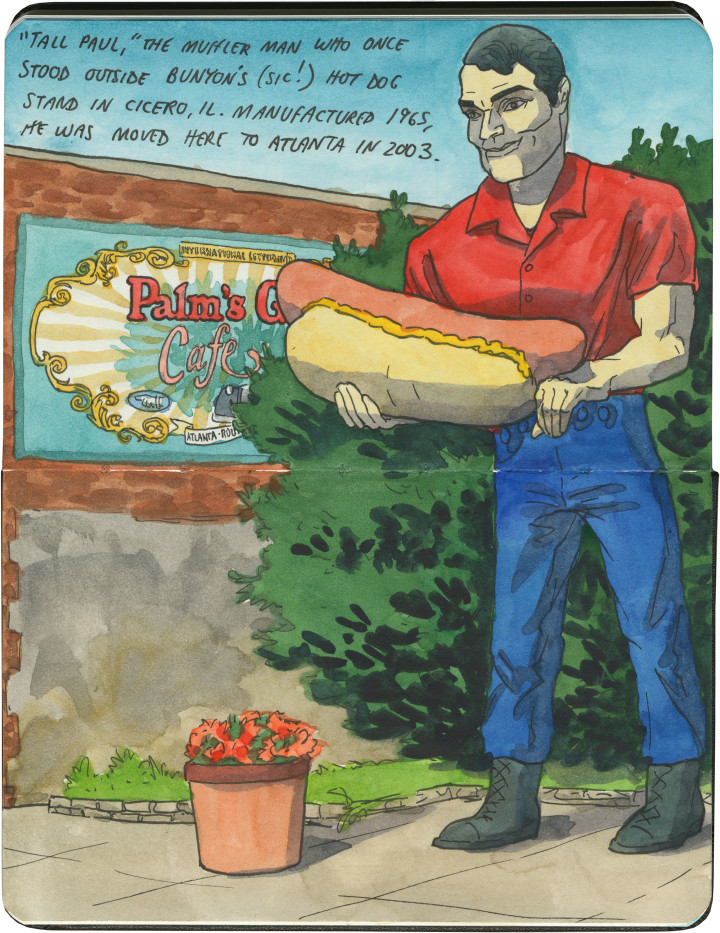

International Fiberglass’s midcentury giants are scattered around the country, and the Muffer Man diaspora certainly includes Route 66, as well. But the fiberglass beefcakes along Illinois’s diagonal streth of Route 66 an extra-special breed. These men are called simply the “Brothers,” and most of them have unusual variants of the standard Muffler Man “physique.”

First up is this rather bizarre guy, currently located in Atlanta, IL. It seems a little random that he’s holding a hot dog rather than the standard muffler (though in my experience, Muffler Men almost never hold actual mufflers these days), but his origin story makes everything clear. You see, this guy, named “Tall Paul,” originally stood outside Bunyon’s* hot dog stand in the Chicago suburb of Cicero. When he was originally commissioned in 1966, the owner of Bunyon’s had him outfitted with a custom fiberglass frank instead of a muffler. After Bunyon’s closed its doors in 2002, Tall Paul was sent “downstream” along Route 66 to the town of Atlanta, where he’s housed on long-term loan. While he looks handsome here in Atlanta, I still wish I could see him in situ in Cicero, amidst his Chicago-dog brethren.

* Bunyon’s, as in Paul Bunyan, except it was purposefully misspelled to avoid any possible trademark infringement.

Next are the fraternal fiberglass twins of the capital city of Springfield. The guy on the left, who admittedly is not right on Route 66 (but not far off of it), is a former Carpet Viking in new garb. And on the right, just a block or two off of the Mother Road, is the Lauterbach Tire Man, now newly re-capitated after a 2006 tornado quite literally blew his head off.

And then there’s the mutant masterpiece of Illinois 66, a particularly odd and endangered specimen known as the Gemini Giant.

This guy stands sentry outside the now-defunct Launcing Pad Drive-in in the town of Wilmington. When he was commissioned in 1965, the owners of the Launching Pad capitalized on the Space Race fad of the era, and customized their guy with an astronaut helmet and handheld rocket. Even his name, devised by a local schoolgirl, referenced the Gemini space program. The result is not only one of the most unusual muffler men, but also one of the most recognized Route 66 landmarks.

The empty Launching Pad property and the Gemini Giant are both currently for sale—they went up for auction just this April, but failed to meet the reserve price. Despite an uncertain future, the town of Wilmington appears to be committed to preserving the Gemini Giant. I certainly hope so—if any of the Brothers were to disappear from Route 66, they’d leave some awfully big shoes to fill.

This post is part of an ongoing series called 66 Fridays, which explores the wonders of old Route 66. Click on the preceding “66 Fridays” link to view all posts in the series, or visit the initial overview post here.

It’s easy to take for granted the fact that the American West is crisscrossed with highways nowadays, but those highways didn’t get there by chance. If you look closely at the routes those highways take, you can give yourself an excellent crash course in history, both human and natural. Overland exploration, trade routes, desert basins, animal migration, continental drift…all these things and more are hinted at by the map sketched out by the U.S. highway system.

Let me explain what I mean. If you happened to grow up in the Midwest, chances are your mental map would be dictated by a grid that follows the cardinal directions. In the Great Plains, particularly, where the landscape is mostly flat, dividing property lines and town borders into a standard grid makes the most sense. Much of the United States west of the Appalachians is arranged this way, in fact, in a basic grid called the Range and Township system. The system overlays a simple framework of one-square-mile sections over the entire western two-thirds of the country, dividing the landscape into rangeland for farming and six-mile by six-mile townships. Interestingly enough, we have Thomas Jefferson to thank for this system, which he devised in 1785 as a way to manage the vast swaths of land that, after the Revolution (and some years later the Louisiana Purchase), now belonged to the U.S. His reasoning, I think, was both practical and lofty: as a farmer himself, he was looking for a workable alternative to the inherited system of Metes and Bounds, England’s age-old framework for managing farmland and water access. While that system worked for the colonies, each roughly comparable in size and topography to what they knew in the Old World, the old framework wasn’t scalable to the size of the new West—particularly when tracts of land were being sold off sight-unseen to settlers and prospectors. But beyond the practical logic, I think Jefferson had more philosophical motives behind his plan. This is the guy who designed Monticello, after all, a monument to neoclassical thinking and an homage to ancient Greece and Rome. The Range and Township system applied a sense of order—however illusory—to the uncharted wilds of the West. It brought rational thought and a sense of opportunity to an area associated with chaos and the fear of the unknown.

If you’ve ever visited the Great Plains, you can still see Thomas Jefferson’s plan in evidence, from the straight-as-an-arrow farm roads in rural areas, to the faithful system of thoroughfares in cities like Tulsa or Dallas, where the roads always travel from A to B in a straight line, with traffic lights appearing like clockwork at precise one-mile increments, and tenth-of-a-mile residential blocks in between.

But here’s the problem: Thomas Jefferson never laid eyes on the West he gridded out like a piece of paper. He never saw nature’s rebuttal to rationality in the Rockies or the Colorado Plateau. It’s all well and good to have a sensible grid in a flat place, without major physical features to interrupt the plan. But in many parts of the West, Jefferson’s tidy squares becomes utterly useless. You can’t easily farm a quadrangle of land that’s bisected by a canyon, and you can’t run a road up and over a mountain. Travel in a straight line is impossible in many, many places. As everyone from Chief Joseph to Lewis and Clark to highway engineers could tell you, there are some places in the West where only one route overland is possible—or none at all.

So if you look at a modern highway map of the western half of the United States, the limitations geography places on rationality are obvious. You can see precisely where the Corps of Discovery found their way to the Pacific Northwest, or where the stagecoaches hauled goods to Santa Fe, or how the Mormon pioneers tumbled out of the mountains to the Great Salt Lake, or the supply route linking the California Missions to Mexico. It’s all there, because centuries later we’re still traveling the exact same routes that humans always have, dodging mountains and following water to whatever their destinations were. The Conestoga wagons followed the game trails and trade routes of the various Indigenous peoples. The railroad followed the pioneers’ wagon tracks. The first pavement slabs paralleled the railroad grade, and modern Interstate freeways zoom right over many of those original roadbeds and trailways. Even the technology of conveyance was based on the older methods of travel—just look at the wheel base on a modern car, whose width matches that of railroad cars, themselves directly descended from the lineage of horse-drawn wagon measurements.

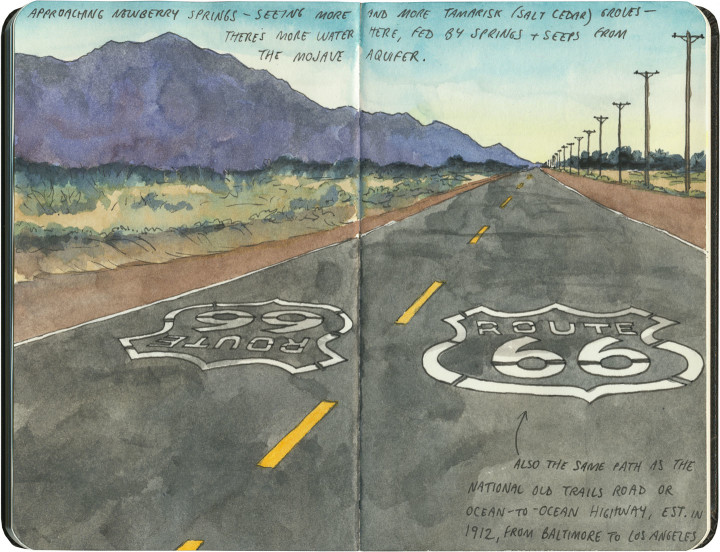

As you can probably guess by my long-winded introduction here, this stuff ties square in with Route 66 and the path it cuts to the Pacific.

There are many places along Route 66 where you can see this progression of transportation history unfold before your very eyes. In flat places like central Illinois or eastern Oklahoma, there was no reason to reuse the same roadbed over and over again—they had all the land in the world at their disposal, and nothing to impede their path. So they simply built the new road alongside the old—over and over again.

The result is a network of parallel lines, each wider than the last, each laid down at a different point in recent history. In these places, the land acts like a palimpsest, marked over and over again with new traceries of roadbeds, while the old ones, though crumbling in disrepair, still remain visible.

Since Route 66 was decommissioned as an official national highway, there are places where it’s difficult to discern the original route. The old roadbed might be there, but the Mother Road can get lost amid a modern tangle of frontage roads, diversions, and replaced pavement.

Part of the joy of traveling Route 66 is learning to recognize the old road. In some places, the path is lit up like a beacon with painted pavement and restored waymarking…

…in others, tracing the original marks on the palimpsest becomes something of a quest.

And then there are the places where the original pavement itself becomes the attraction along the way—like this gorgeous stretch of brick roadway in Illinois, paid for in the 1930s by a brick magnate and lovingly maintained as a curious relic of the past.

My favorite of all was the long section of 66 that traverses central Oklahoma: the combination of good craftsmanship and a remote locale has preserved the original roadbed impeccably. It sounds nerdy to say it out loud, but I dare any 66 enthusiast not to feel a thrill when seeing that curbed Portland cement.

By the end of our journey, we’d gotten really good at spotting the difference between old and new along the way. And whenever we lost the thread of the route (easily done, since there are so many alignments, many of which have been replaced or buried under modern roads), it became easier and easier to spot the hints that would lead us back to the Mother Road.

What led me to travel Route 66 was a love of history and Americana, and a desire to travel a well-worn and well-loved path. I had no idea that it would be so much more—and something much closer to the feeling of solving a mystery. Beyond the fun of diners and neon, there’s a richer, subtler 66 to be discovered, if you’re willing to look a little deeper. All the clues are there—some of them stamped right into the pavement underfoot.

Well, I guess if you sell hot dogs, it’s pretty hard to compete with the frankfurter meccas of Chicago and New York, where they have mastered every wiener gimmick known to man. Still, if you set up shop in a small town like Lindstrom, Minnesota, you don’t exactly have to work too hard to stand out.

I’m glad these folks don’t seem to have gotten that memo, because this place just charmed the heck out of me. I mean, go big or go home, right?

This post is part of an ongoing series called 66 Fridays, which explores the wonders of old Route 66. Click on the preceding “66 Fridays” link to view all posts in the series, or visit the initial overview post here.

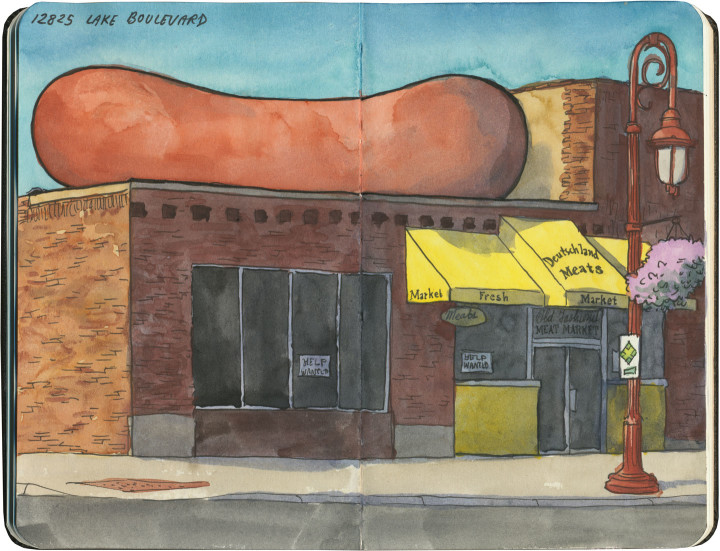

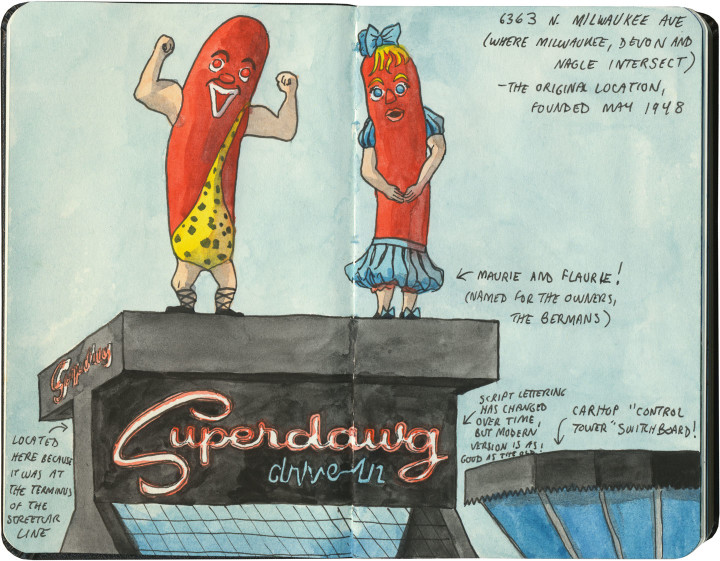

Okay, I’m starting this post with a few sketches that are not on Route 66, but that provide a good bit of context—which is to say, if you’re hankering for a roadside red hot on your travels, there’s no better place to go than Chicago.

There’s some debate as to the origin of the humble hot dog. There is the German frankfurter, of course, but what has become the ultimate American street food seems to have murkier beginnings. Various cities with German-immigrant roots lay claim to the invention, including New York (where sausages were served on rolls at Coney Island in the 1870s) and St. Louis. But thanks to the persistent legend that the modern dawg, as we know it, was first served at the World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893, Chicago has taken the story and run all the way to the bank with it.

Today, Chicago is the weenie capital of the world. Chicagoland Mom & Pop hot dog stands outnumber the city’s combined tally of McDonald’s, Burger King and Wendy’s franchises. And many of them, like the fabulous (and slightly creepy) Superdawg Drive-In above, have been mainstays for half a century or more.

And just like the infamous Hot Wiener Sandwich of Rhode Island, a true Chicago Dog wouldn’t be caught dead in ketchup.

I started with these non-66 hot dog stands so you could see how high Chicago sets the bar for its tube-steak signage. If these wiener masterpieces could be found across town from the Mother Road, imagine how high my expectations were for Route 66’s offerings.

Well, I’m here to tell you, I didn’t come away disappointed.

And if you’re heading west on Route 66, you’re in for an added bonus. Just when you think you’ve left the Dog Days behind, you’ll reach the state capital of Springfield and meet the Cozy Dog Drive-In. The Cozy Dog was founded by one Ed Waldmire, Jr. (remember the name Waldmire—there’s more 66 lore there to share another day), who, at a USO during World War II, invented the “crusty cur,” a cornbread-battered hot dog on a stick that would become a staple of State Fair cuisine. The recipe was an enormous hit with the troops, so in 1946 Waldmire rechristened his creation the Cozy Dog, and the rest, as they say, is history.

This post is part of an ongoing series called 66 Fridays, which explores the wonders of old Route 66. Click on the preceding “66 Fridays” link to view all posts in the series, or visit the initial overview post here.

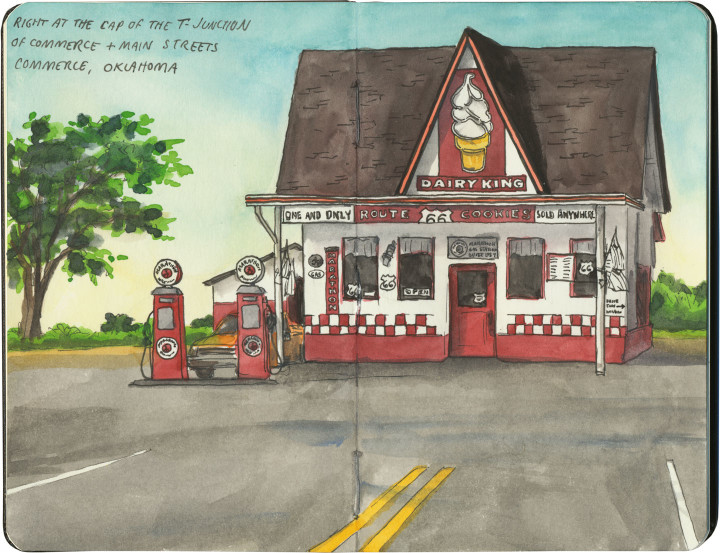

If you happen to drive Route 66 in the summer, like we did, you might just find yourself pulling into Commerce, OK at the hottest part of an absolutely scorching day. If that’s the case, this former filling station will appear on the horizon first like a desert mirage, and then like a beacon of hope.

Apparently the unique draw of the Dairy King is the legendary Route 66 cookie (yes, a cookie shaped like US Highway shields!), but I have to confess: sometimes all you want on a hundred-degree day is a little something frosty.

This post is part of an ongoing series called 66 Fridays, which explores the wonders of old Route 66. Click on the preceding “66 Fridays” link to view all posts in the series, or visit the initial overview post here.

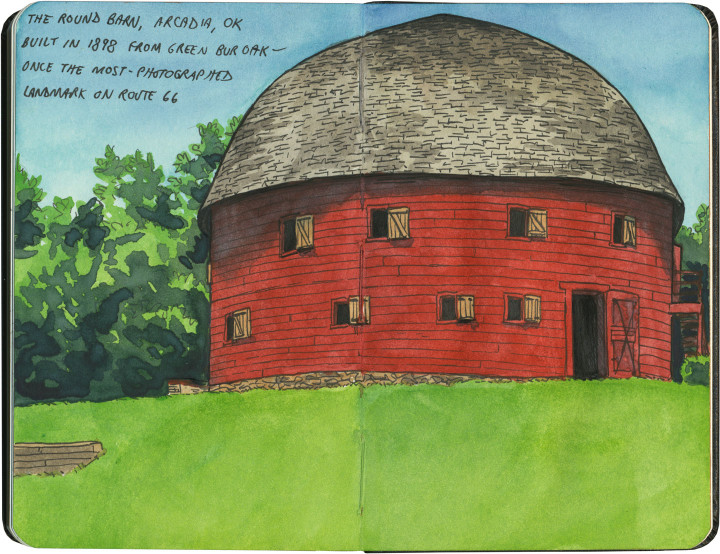

Last Friday’s post was a bit of a downer, I know. So today, as we move into the Sooner State, it seems like a good idea to visit a real beauty of the Mother Road: the Arcadia Round Barn. Built out of green wood carefully bent into precise curves, the barn is the only truly round (and not polygonal) barn in America. Its unique status and beautiful proportions made it the most photographed landmark on Route 66.

It was hotter than blazes in the loft, but well worth suffering the heat. Because up there, surrounded by all that curved wood and perfect geometry, it felt more like the work of a Renaissance master than a humble farmer.

This post is part of an ongoing series called 66 Fridays, which explores the wonders of old Route 66. Click on the preceding “66 Fridays” link to view all posts in the series, or visit the initial overview post here.

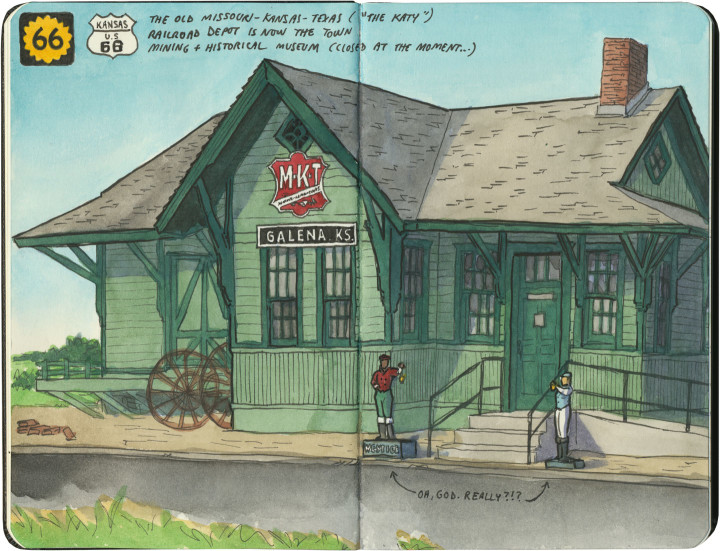

Logically, if you were to plan a trip from Chicago to Los Angeles, the shortest route would have you traversing Kansas to get there. Yet Route 66 carves out just 13 miles of road in the state’s southeastern corner, and does the bulk of its crossing of the Great Plains through Oklahoma instead. Why, you ask? Well, that’s an interesting story. The man responsible for plotting the Mother Road’s path, Cyrus Avery, called Tulsa home. He wanted to show off his state in all its glory, so he made Route 66 both a tour guide and a monument to Oklahoma, with over 400 miles of pavement to draw travelers and tourist dollars there. Still, Kansas gets a small slice of the action, and this gorgeous early-1900s train station does the Sunflower State proud.

There’s something else about this sketch that needs some explaining. See those small figures flanking the front steps? Yes, those are lawn jockeys. I could have just left them out of the sketch entirely, since I personally find lawn jockeys offensive and I hate to single out Galena. But I didn’t, because they bring up an uncomfortable truth about travel Americana, and the Mother Road in particular.

While it’s easy to get wrapped up in the nostalgia of olde-tyme family road trips and midcentury diners along Route 66, that part of American history is really only quintessential to the white population of this country. Black Americans, in particular, didn’t travel Route 66 the way white ones did. In many places, it simply wasn’t safe for them to do so. These places had a name that most of the nostalgic Mother Road literature seems to have forgotten: sundown towns.

Sundown towns—communities that barred people of color from the town limits after dark—were by no means confined to the South, nor did they exclude only African-Americans (my own city of Tacoma, WA expelled its Chinese residents in 1885). Sundown towns could be found everywhere from Connecticut to California, and even as late as the 1960s there were thousands of them. Thankfully Galena, as far as I can tell, was not among them—I should make that clear, since I’m already featuring that town in this post. Yet sadly, there were many sundown towns along Route 66—particularly in Oklahoma, Illinois, Missouri and California. In fact, for thirty years Black travelers relied upon the advice in The Negro Motorist Green Book, a guidebook printed between 1936 and 1964, which outlined which routes, communities, services, restaurants and lodging were willing to serve road-trippers of color. The Green Book mostly sent travelers well away from Route 66 and its many Jim-Crow-era dangers.

This history is all but scrubbed from the modern remnants of the Mother Road. If I hadn’t seen those lawn jockeys, I might not have thought to look into it myself. Yet unfortunately, there is also some fresh modern racism along 66. (We were particularly horrified by the large number of Confederate flags we saw along the route, mostly in western Arizona.) You’ll never see a sketch of that sort of thing on this blog, but I feel it’s important to note that it’s out there, that the Mother Road is not all neon and nostalgia. After all, you know what they say about those who don’t learn from the past.